A woman's point of view

A new exhibition sheds light on how women photographers see – and depict – other women

The history of photography is largely an encyclopedia of the male gaze.

The photographers most often discussed since the advent of the craft have tended to be men. Yet, given photography’s relatively short life, women have been practicing it, more or less, since the beginning.

“Into the Light,” a new photography exhibition at Daniel Cooney Fine Art, effectively casts the male gaze aside with photographs of women, by women. The show presents a sweeping historical view of women photographing women from the mid-18th century to the present day. Through portraits, self-portraits, street and documentary photographs, “Into the Light” presents a view of women decidedly more empathetic and celebratory.

“There’s a respect and a sense of responsibility for how they’re presenting somebody else’s image,” curator Daniel Cooney said of the photographers in the exhibition.

The show is notable for how it is providing a space for women — 26 photographers in all — from myriad backgrounds to tell stories about women.

Fresh air

“The show is a breath of fresh air to be in a room with so many incredible female artists,” said Kia LaBeija, a photographer who has a self-portrait in the show.

In her image, LaBeija is seen in a bright red dress standing in front of an examination table. She holds a white rose while a doctor stands next to her with a syringe at the ready. The doctor is LaBeija’s doctor, and the dress is her prom dress.

The image is part of a larger body of work in which LaBeija explores her experience living with HIV, which she has had since birth.

There is a quiet, contemplative quality to the photo that is counterbalanced by the vibrant splash of color with the light focused squarely on LaBeija in the center. Solemnity and joy command the frame.

“That feeling of vibrancy is something that I really love,” LaBeija said, recalling the color palettes of Disney films and the chromatic brand Lisa Frank. “I wanted it to feel incredibly vibrant no matter what kind of difficulties I faced.”

This day and age

While the show is decidedly apolitical, it comes at a time when political forces are crashing against each other, from the cathartic conversations that have arisen out of the “Me Too” movement, to the views espoused by the current administration and the potential transformation of the Supreme Court. These political realities formed the backdrop of what led Cooney to put the show together at his West 26th Street gallery.

“With the current political climate, it’s something that’s on my mind,” Cooney said. “If Hillary was president, it wouldn’t be on my mind so much.”

Even though politics might find its way into the discussion, the show is about women and how women see each other.

“I want it to be a celebration of what women have contributed throughout history to the practice of photography,” Cooney said.

One of the earliest photographs in the show is Julia Margaret Cameron’s 1874 portrait of actress Isabel Bateman in costume as Queen Henrietta Maria. In quiet repose, Bateman gazes directly at the camera, giving the image a certain intimacy as though she and the viewer are in the same space.

New directions

It was crucial for Cooney to find a balance between historic and contemporary photographs. The historic images prove women have practiced photography for quite some time, where as the contemporary work shows how women have taken the craft in new directions.

For the last several years, photographer Annie Tritt has worked on “Transcending Self,” a project that explores the lives of transgender and nonbinary youth, with two photographs from that project part of the Cooney exhibition. One is a portrait of a 17-year-old transgender girl named Azaj, and the other is a portrait of a 12-year-old transgender girl named Lill.

In Azaj’s portrait, she stands in front of a fence overgrown with plants. Her expression is both vulnerable and serene as she claims her space in public. In Lill’s portrait, she reclines in bed in her room. Here, too, there is a degree of vulnerability in how she opens herself up.

“You don’t need to pose for me,” Tritt recalls telling Lill. “I just want you to be you.”

Through her project, Tritt has helped to amplify the voices of those who are both navigating their identity and their place in society. She looks at a critical time in their lives through an uncritical lens.

None of the photographers in the exhibition look at their subjects critically. The photographs have a deep sense of empathy, and in some cases, curiosity.

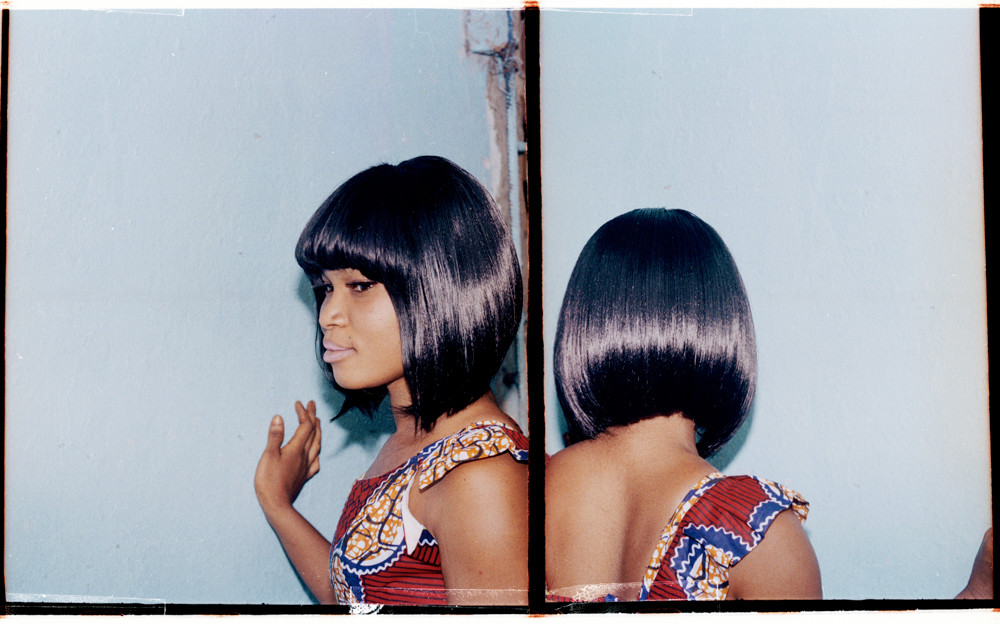

In Émilie Régnier’s project ‘Hair,’ women in the African city of Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, flaunt their hairstyles that defy convention. Régnier sought to push past her preconceived Western notions of what hair could be and found women throughout salons in Abidjan who styled their hair free of societal constraints.

“I became enchanted by what I saw,” Régnier said, “by how those women were influenced by Afro-American stars, but also by how they redefine those aesthetics into something that was more culturally in-tune with how they conceived beauty.”

Régnier has two photographs from ‘Hair’ in the exhibition — both diptychs — showing each woman’s hairstyle from two different vantage points. In one, an explosion of lustrous and lively blonde hair is shown from the front and the side. In another, a jet black bob is shown from the side and the back.

These images of hair are a part of the exhibition’s kaleidoscopic portrait of women. It is comprehensive both historically and existentially, and it depicts women in a way that only women can.

“It’s important that other people tell other people’s stories because other people can see what we can’t see,” Tritt said. “But we’re tired of that perspective.”