Anthony Friedkin's love letter to the wave

In the cathedral, nothing else matters.

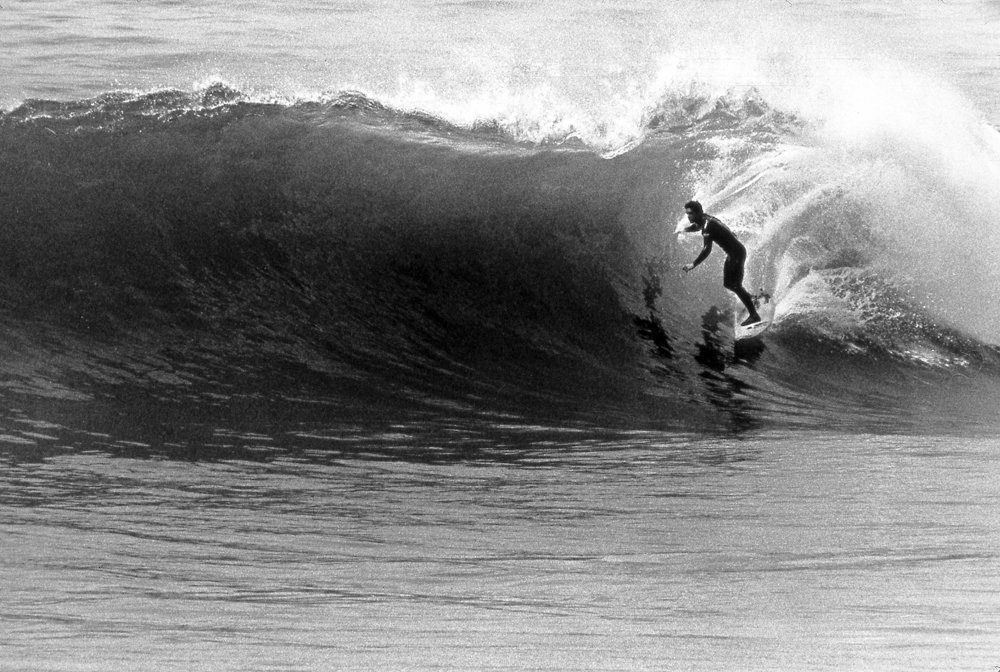

The cathedral is, of course, what surfers call the tube that forms when a wave breaks. It’s a space that Anthony Friedkin has found himself in countless times over the course of more than 50 years in southern California.

“Space and time change,” Friedkin says of the experience inside the cathedral. “Your surfboard’s moving. You’re moving. The wave is moving.”

It is transcendental and ephemeral. Surfing is a constant pursuit of the sublime, and it is intrinsic to who Friedkin is, both as a surfer and as a photographer.

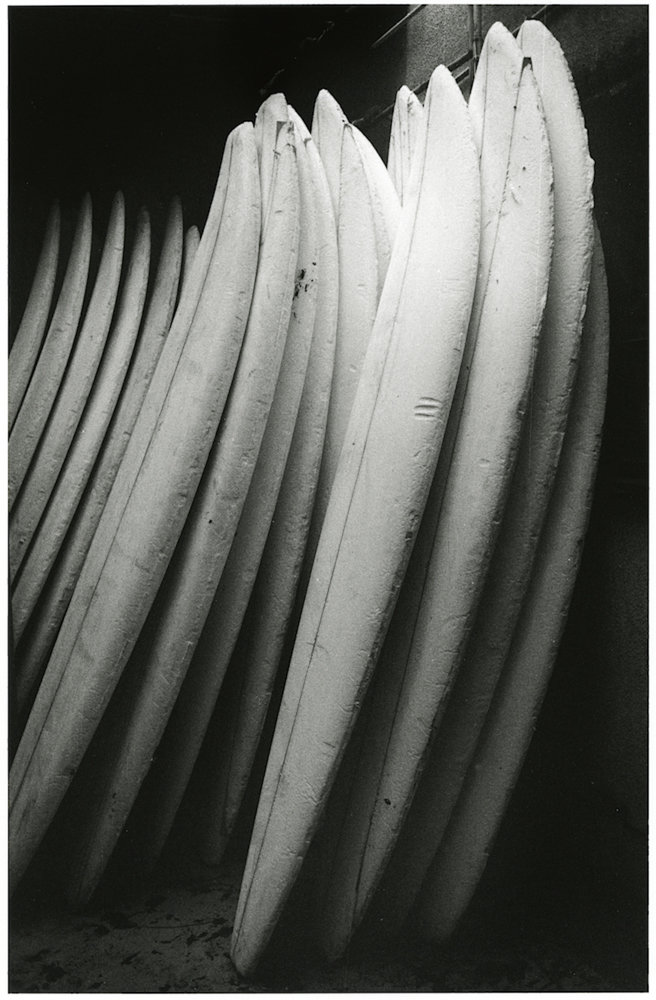

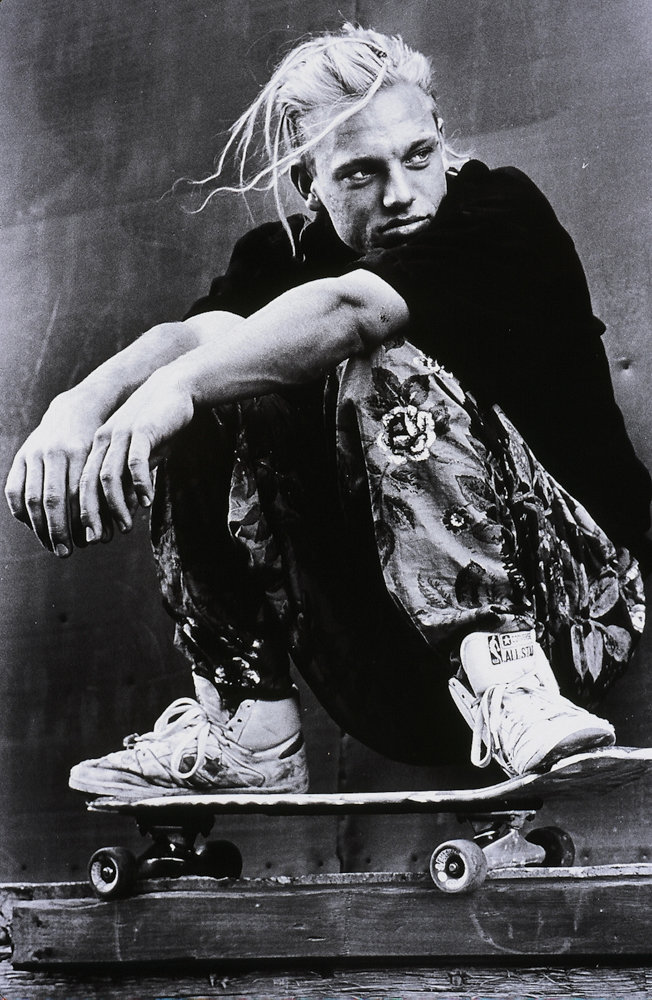

A new exhibition of Friedkin’s work, “The Surfing Essay,” is on display at Daniel Cooney Fine Art through Dec. 21. The photographs document a community Friedkin has known for most of his life. Shot on black-and-white film, they capture a place and community almost completely outside of time.

It is often said there is a certain timelessness to black-and-white photographs, and that maxim holds true for Friedkin’s work. An image from 2008 and one from 1968 could be interchangeable. There are barely any signifiers of the time in which they were taken, save for a billboard advertising a particular beverage, “Quaalude & Coke.”

In the gallery, there are no caption placards accompanying the photographs, which deepen their timeless feel. For those curious, there are some catalogs that provide supplementary information.

Beyond stereotypes

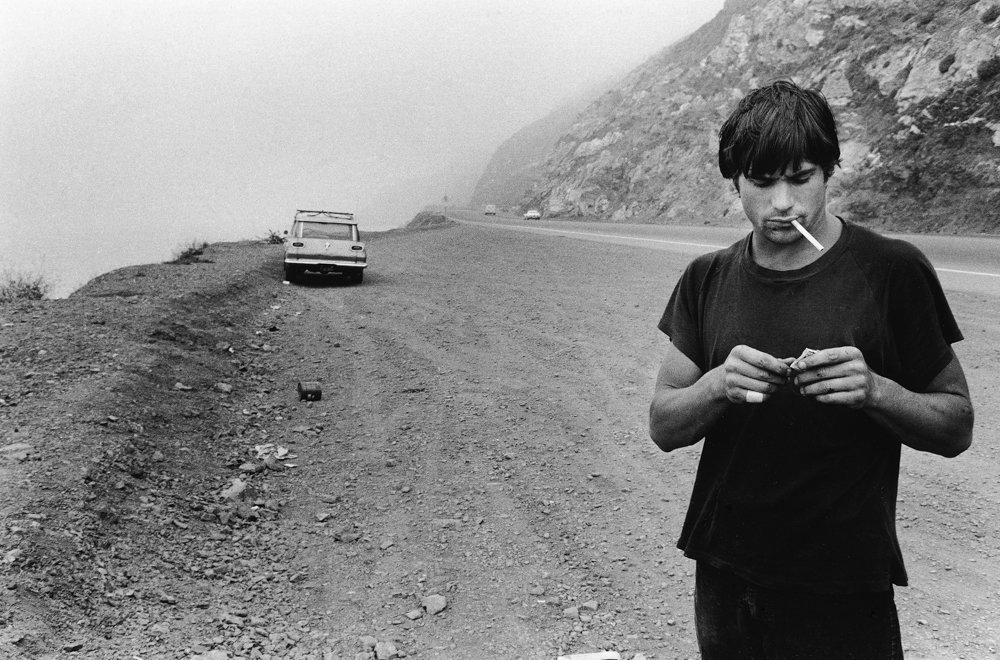

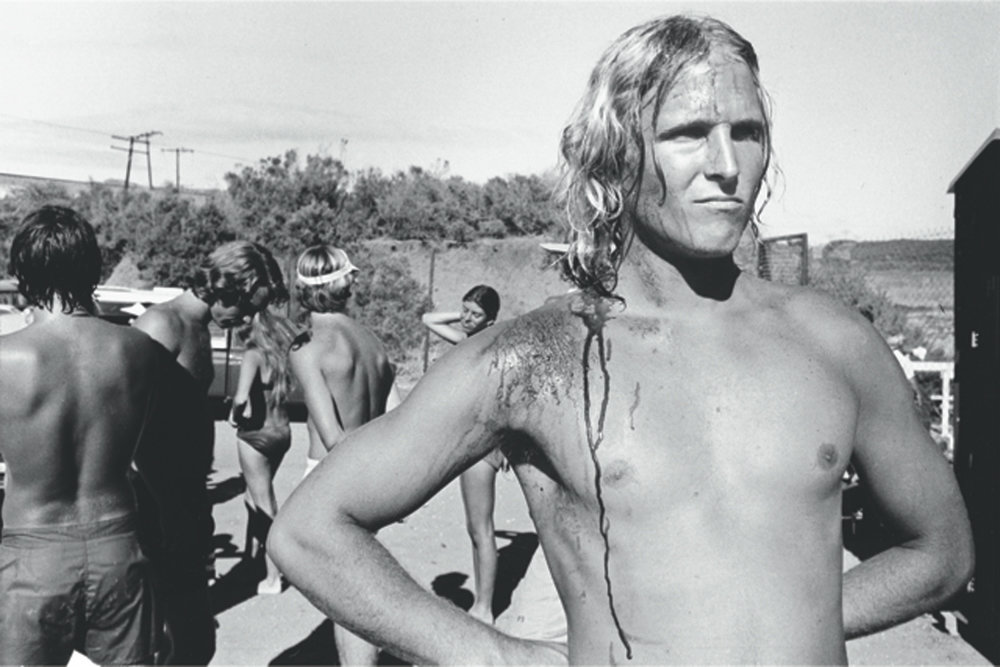

The photographs themselves are experiential, telling a complicated story about the surfing community in southern California. The stereotypical surfer is a feel-good, suntanned, beach blond guy with a lean build. Hollywood has played a large part in popularizing surfing culture, going back to the 1959 film “Gidget.” But these popular renditions of a community Friedkin lives and breathes miss the mark entirely.

“They never revealed the kind of life I was living with my friends,” the photographer said.

The truth in his pictures is grittier and far more interesting. Surfers party. They do drugs. They have sex. They get hurt. They pick themselves back up. Oh, and they surf, too.

“I haven’t seen many photographs like this about surfing,” said Daniel Cooney, the curator of the exhibition. “I’ve seen lots of pictures of surfing, but they’re usually more idyllic or beautiful. This shows me that surfers were punk rock.”

Friedkin eschews artifice and conventional notions of beauty in favor of a verité style of storytelling. His photographs are the windows through which we can look at his world.

“The singular act of perception is such a (expletive) miracle,” Friedkin said.

When he was younger, there was a time when Friedkin would intentionally make himself deaf, or as close to deaf as possible, in order to heighten his vision. He would plug his ears with wax in order to focus on taking the world in visually, because photographs are a silent experience. While they can unlock myriad sensations in the viewer, the photograph itself is silent.

A story to tell

How he sees is crucial to his practice as a documentary photographer, and he works in the tradition established by the likes of Danny Lyon, Robert Frank and Margaret Bourke-White.

“It’s going to have a story to tell, almost like a split-second movie,” Friedkin said of documentary photographs.

That cinematic aesthetic is present in all of his images, from the earliest to the most recent. They are a testament to both his vision as a photographer and his commitment to his surfing community.

Friedkin has worked outside of his community, too. “The Surfing Essay” is his second exhibition at Daniel Cooney Fine Art. His 2017 show, “The Gay Essay,” brought together images Friedkin took of the gay community on the west coast between 1969 and 1973. While Friedkin is not gay, he earned the trust of the gay community, producing a sensitive and compelling body of work.

That sense of understanding is present throughout “The Surfing Essay.” Since he began surfing, Friedkin saw a community that was inclusive.

“In water, everybody’s the same,” Friedkin said. “It’s how you surf, how well you surf.”

While Friedkin’s vision has remained consistent, his approach to the kinds of pictures has changed over time. This exhibition comes 50 years into the series. The work itself — and the way he thinks about his work — would have been different five years in, or even 25 years in.

“My instincts are a little more refined about how to respond,” Friedkin said, “whether it’s a portrait of my friends, or a moment in the ocean that I found.”

The moment is crucial, both in photography and surfing. A split second makes a world of difference in whether or not a photographer captures the scene, or a surfer catches the wave.

“Waves have very specific moments,” Friedkin said. “There’s a certain fearless attitude about surfing that if you don’t go for it, you’re going to miss one of the greatest thrills of your life.”

It all comes down to the wave, which is what Friedkin loves the most in surfing — both catching and capturing them.

“I could shoot waves for the rest of my life,” Friedkin said.

“They’re so beautiful.”