Where structure meets nature on the river

Harry Wilks’ unique perspective is on display at the Hudson River Museum

Harry Wilks has spent a lot of his time being in places he isn’t supposed to be. But it’s OK — it’s in the name of art, after all.

With large buildings and colossal bridges acting as his muses, Wilks has been escorted by police away from areas he shouldn’t be. But then again, the photographer might just do it again if it means getting the perfect angle for his shots. And his creativity with wide-angle lenses and zoom knows no bounds.

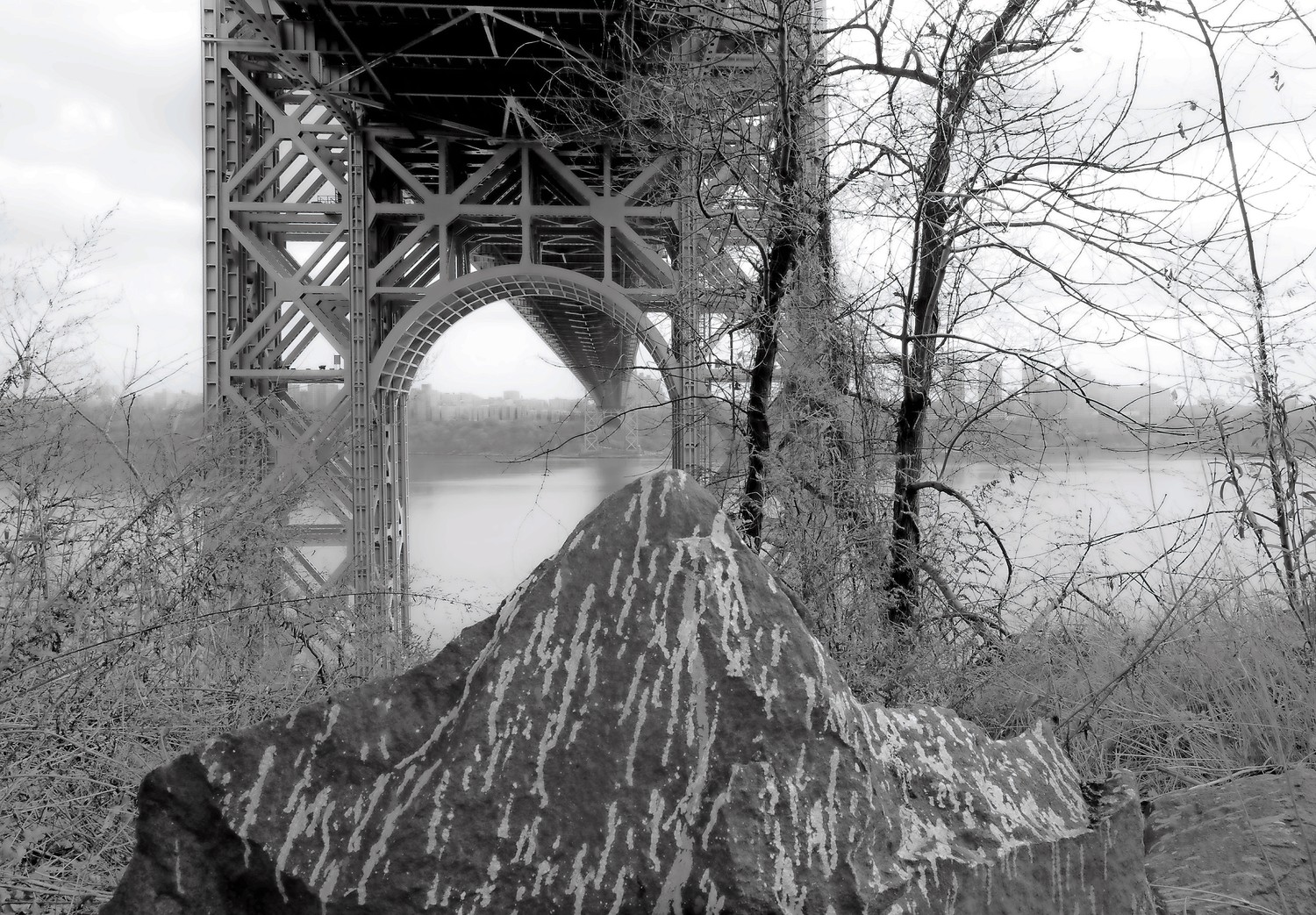

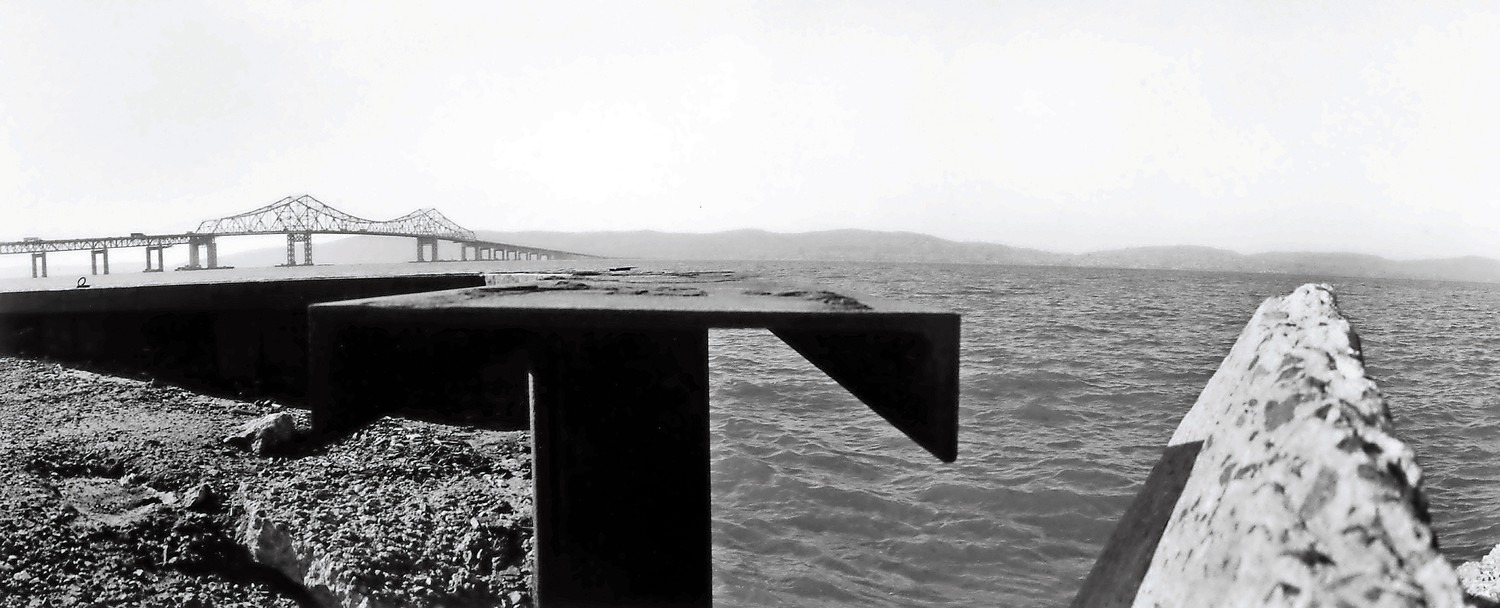

“I purposely took a beautiful Hudson River landscape photo and I put one-third of the girder in it,” Wilks said. “Someone looking at that picture would care to know where I am, and it throws people’s perception off balance.”

Wilks small run-ins with law enforcement have paid off, and now he’s sharing his photographic work in “Harry Wilks: Hudson River Bridges” at the Hudson River Museum in Yonkers.

For Wilks, the Hudson River is more than a landscape worth photographing. The bridges, roads and train tracks that crisscross the river offer a lot for him to work with. Wilks isn’t afraid to get close shots of his bridge subjects so he can achieve an altered image that skews reality.

The Hudson has been a subject of his work for the past 30 years, and makes up a substantial part of Wilks’ collection.

Wilks appreciates the relationship between man-made structures and nature. He spent time photographing railroad tracks and industrial marvels like the George Washington and the Tappan Zee bridges. But the Manhattan native also has found his way up to Spuyten Duyvil to photograph the bridge there.

“I have an affinity for guardrails, and you’ll see them in a lot of the images that I show,” Wilks said.

He counts the famed Lee Friedlander as one of his favorite photographers because he shoots things that appear to be nothing but still manages to make an impressive work of art out of them.

As a self-taught photographer, Wilks spent a lot of time at galleries and museums learning what makes a good picture and what makes a boring one. Using that research, Wilks gathered what he felt were his most exciting pictures and now has them shown in multiple galleries all over the country.

His exhibit at the Warburton Avenue museum runs through Oct. 14. Wilks also will host a gallery talk at the museum Sept. 15 at 2 p.m.

Art always has been part of Wilk’s life. He went to City College of New York where he majored in art and later worked in architecture.

“I started taking pictures when I got tired of drawing straight lines,” Wilks said. “I was an architectural draftsman, but then I just went out with a camera as a self-taught photographer and looked at pictures and figured out what I wanted to do.”

But it wouldn’t be until 1970 that Wilks actually called himself a photographer. Wilks has been shooting for more than four decades and supports himself by taking portraits for companies and selling his prints.

But Wilks isn’t the only one in his family with an appreciation for aesthetics. His wife, Tamar Zinn, is a painter, and his son is an architect. Wilks blames the countless discussions he and his wife had in front of their son about visuals and imagery for getting him into an artistically creative field in the first place.

Another of his projects is more of a personal one. Each year over 31 years, Wilks took a photo of his wife and son resting on their car dressed in her same black dress, and their son more or less in the same pose that was later published in a book. It’s part of his broad take in art, and something that carries him beyond bridges.

“I’ve always been interested in art and architecture, and till this day, I look at buildings,” Wilks said. “When I’m not photographing bridges, I’m photographing buildings and I’m learning what buildings are supposed to look like photographed.”

Throughout his work, Wilks has used a Widelux camera — a swing-lens panoramic camera that stopped being produced at the start of this century — to create a distortion of scale through different exposures, which gives him unmatched results.

“I love landscape, and I love things that man makes, and I try to combine the two together,” Wilks said. “I-t’s not enough to take a picture. Taking beautiful landscapes doesn’t do much for me and I have to put something in that man has built. So I get in my car with my equipment, and I go to places where there’s water and bridges and train tracks, and these are the kind of places I enjoy being.”