A photographic history of gay, lesbian writers

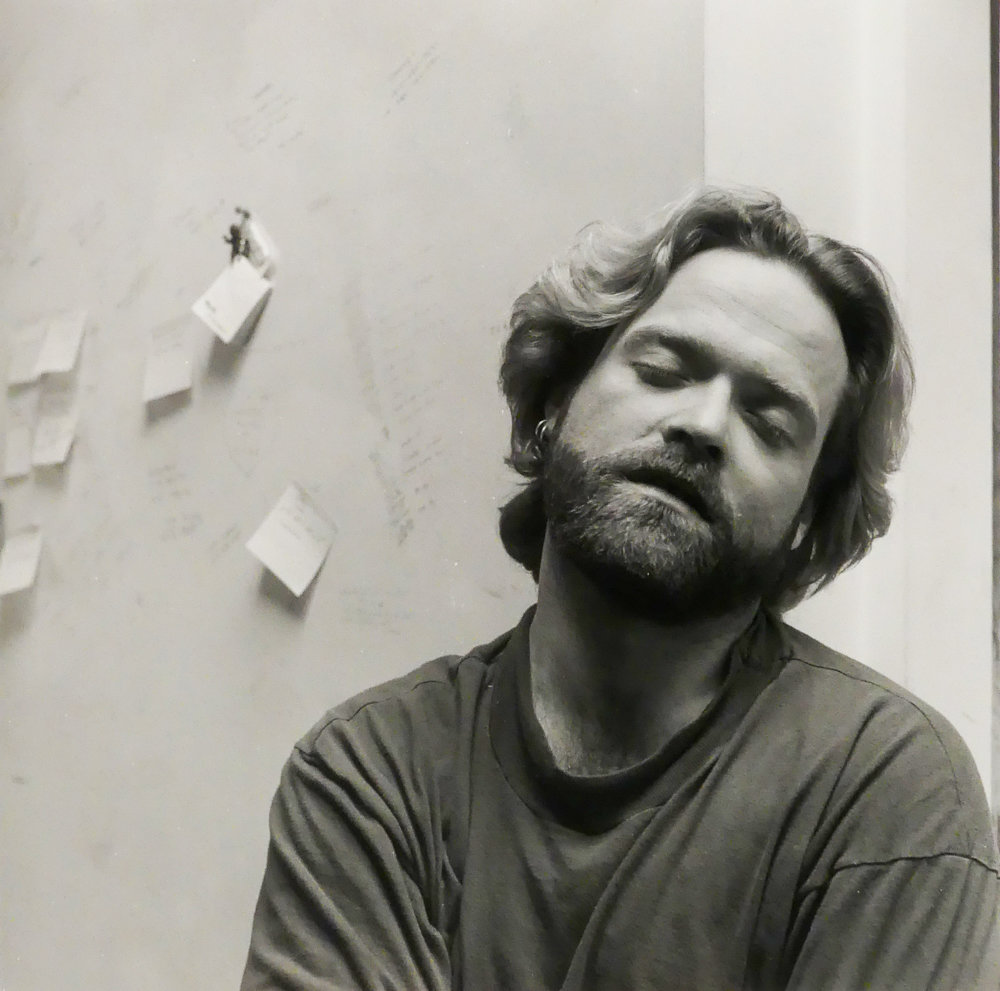

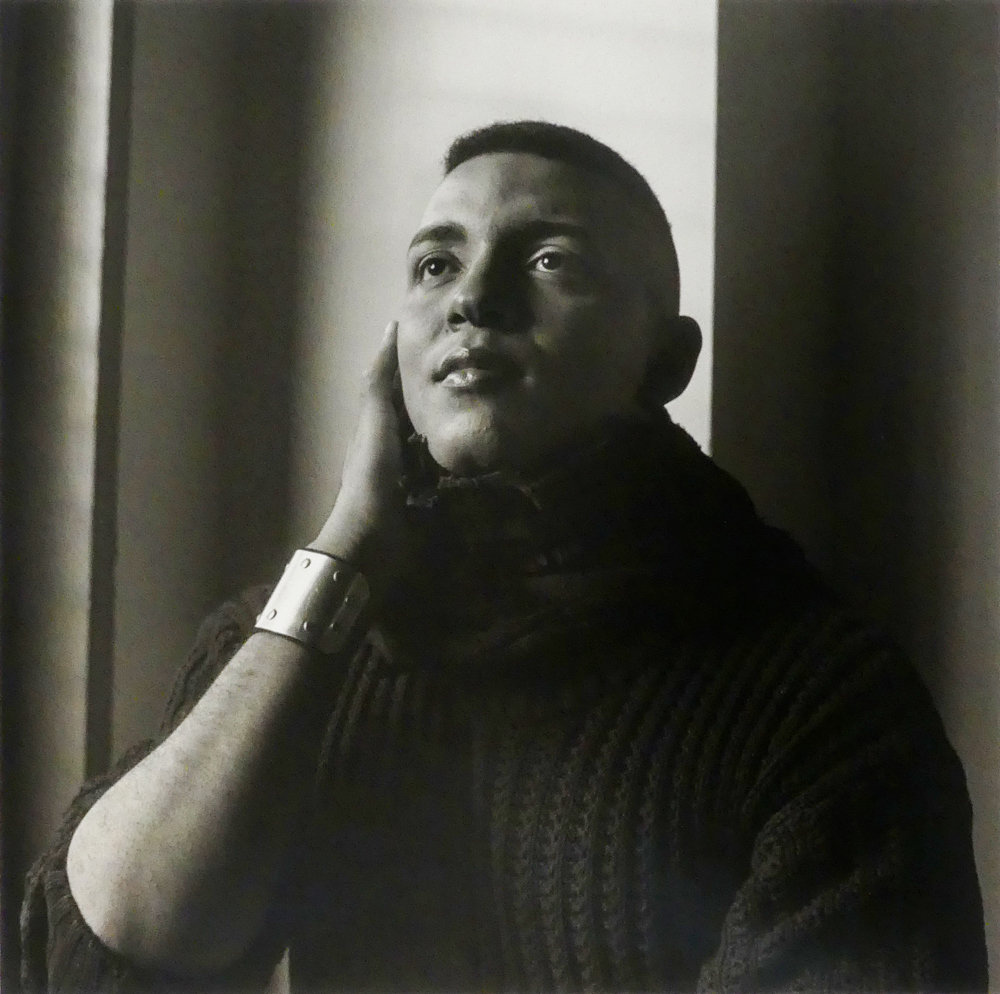

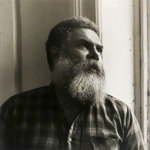

When Michael Klein looks back at his portrait from 1988, the memory is bittersweet.

“I’m not that person,” he said.

Klein was early in his writing career when photographer Robert Giard first contacted him about a portrait. It was a significant transitional period in his life. Newly sober and “terminally single,” as he says, Klein jumped at the chance to be photographed by Giard.

“I was just starting out as a writer,” Klein said, “so I said yes to everything at the time.”

That experience yielded an oneiric monochrome portrait. Klein’s eyes are closed as he leans to the right side of the frame. The wall behind him is flecked with Post-it notes, each containing a friend’s phone number, as it was long before the advent of cell phones.

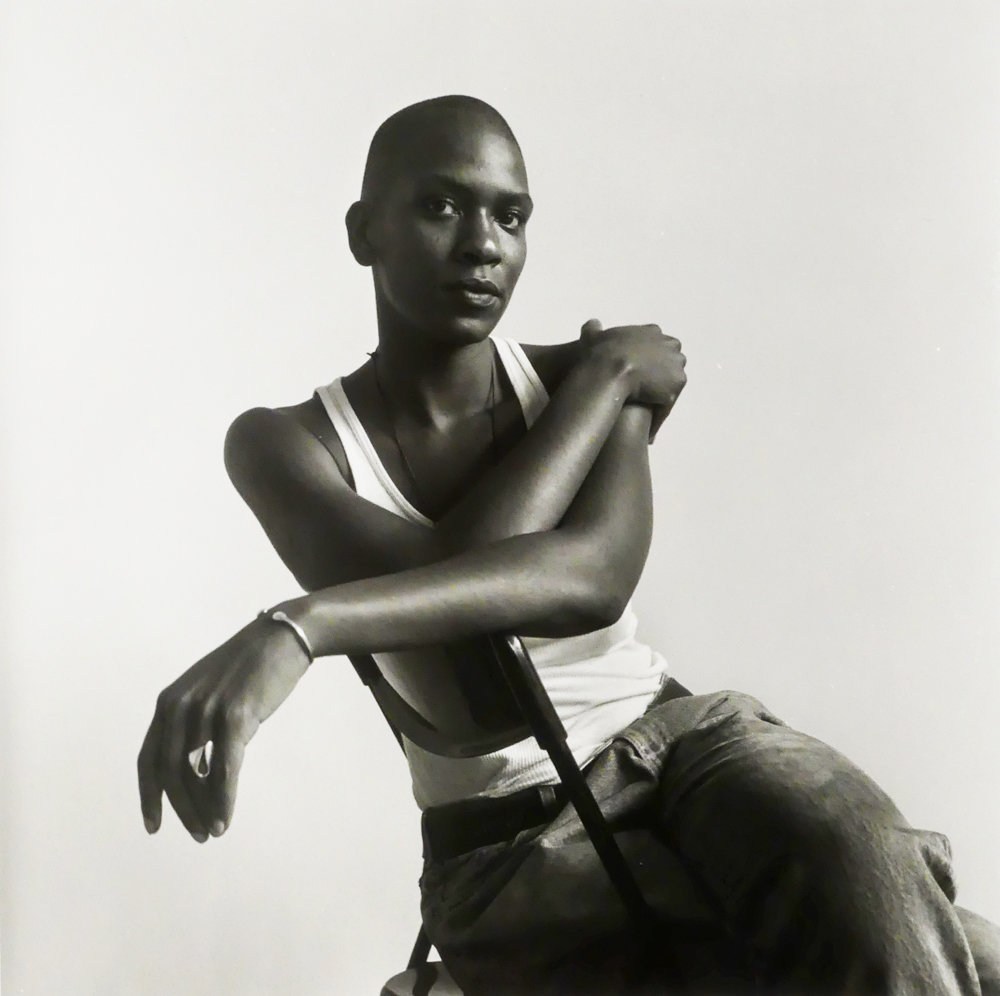

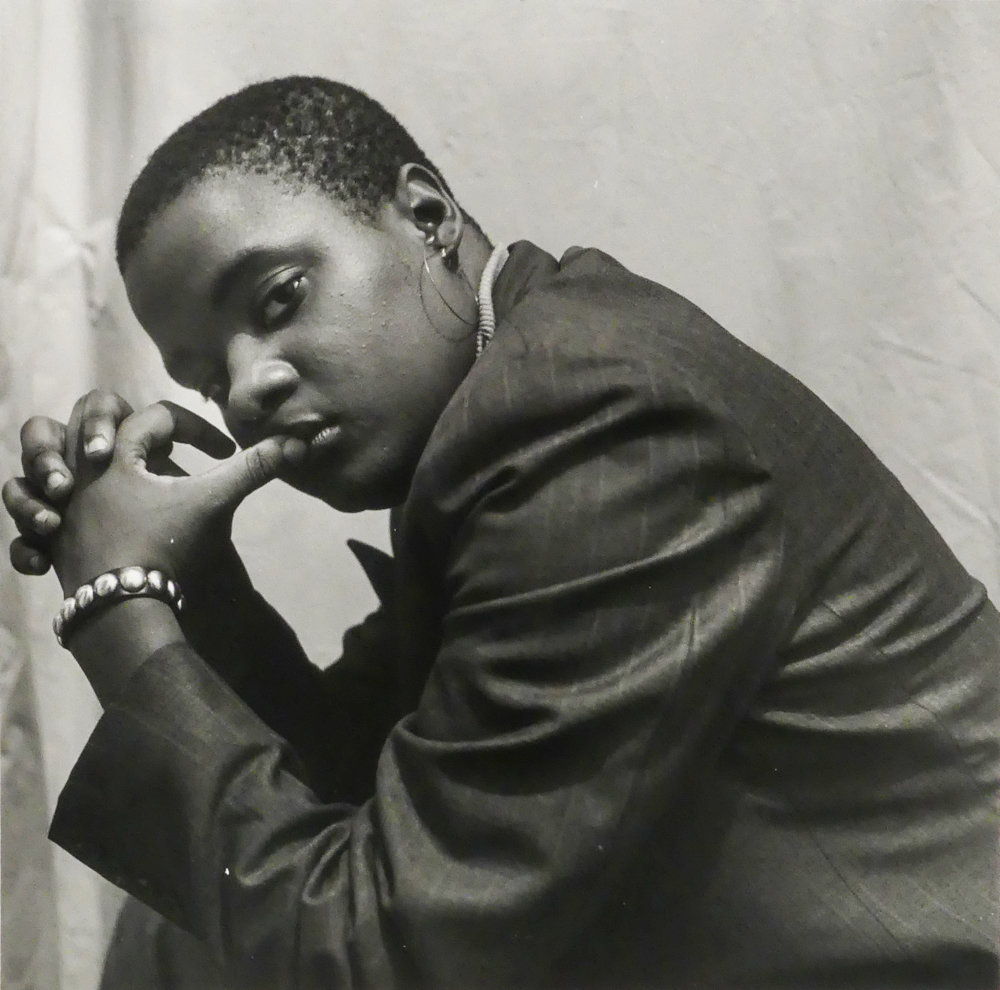

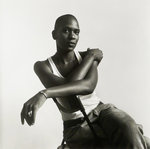

At the time, Giard was several years into what would become a decades-long project to photograph LGBTQ writers, artists and activists. A new exhibition of his work, “Particular Voices,” is on display at Daniel Cooney Fine Art through July 26.

Literature was Giard’s first love. Photography came later, but it was through that visual medium he could show that love. As a gay man himself, Giard was interested in the work of gay and lesbian writers.

“He never went to photograph someone without reading their work,” said Jonathan Silin, a writer and Giard’s partner of more than 30 years.

By reading their work ahead of time, Giard developed an understanding of whom it was he would eventually photograph. It was a way to build a connection and foster trust. The process of making each portrait was deeply collaborative.

“When he would get to somebody’s front door, immediately Bob’s eyes were working the room,” Silin said.

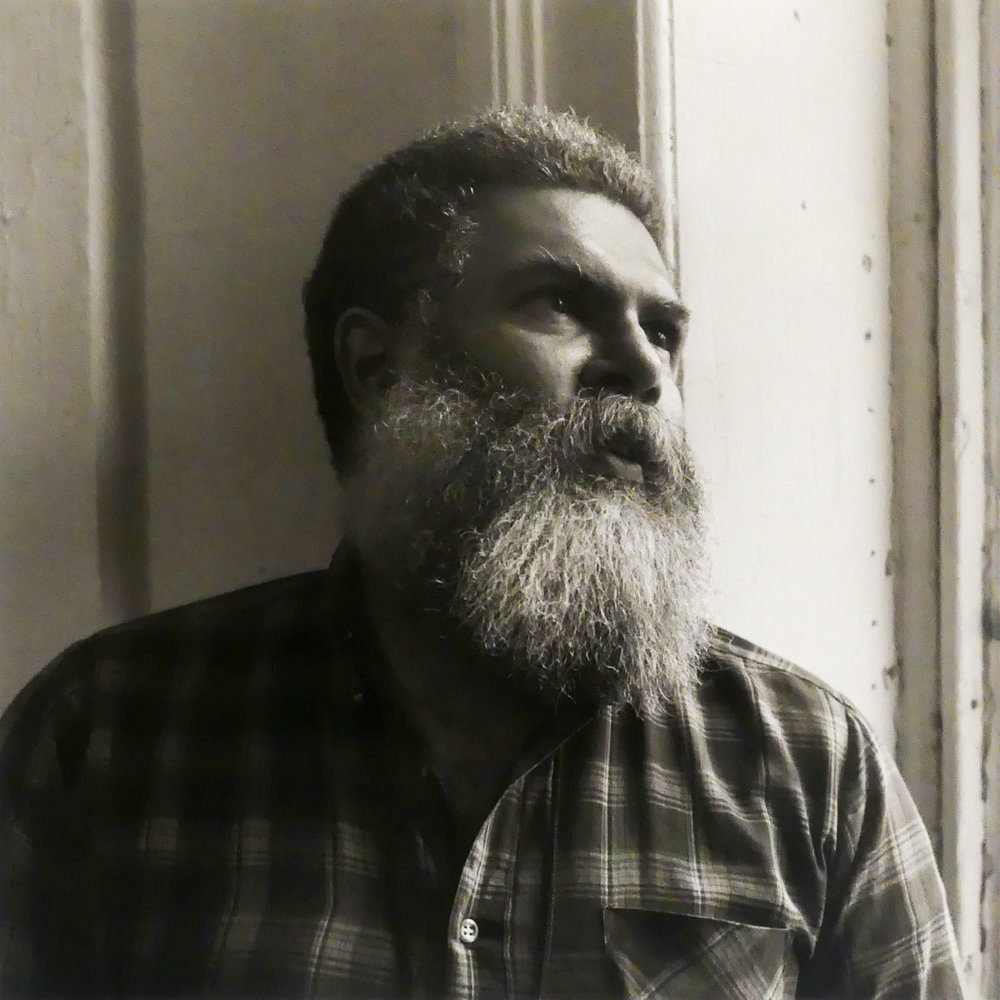

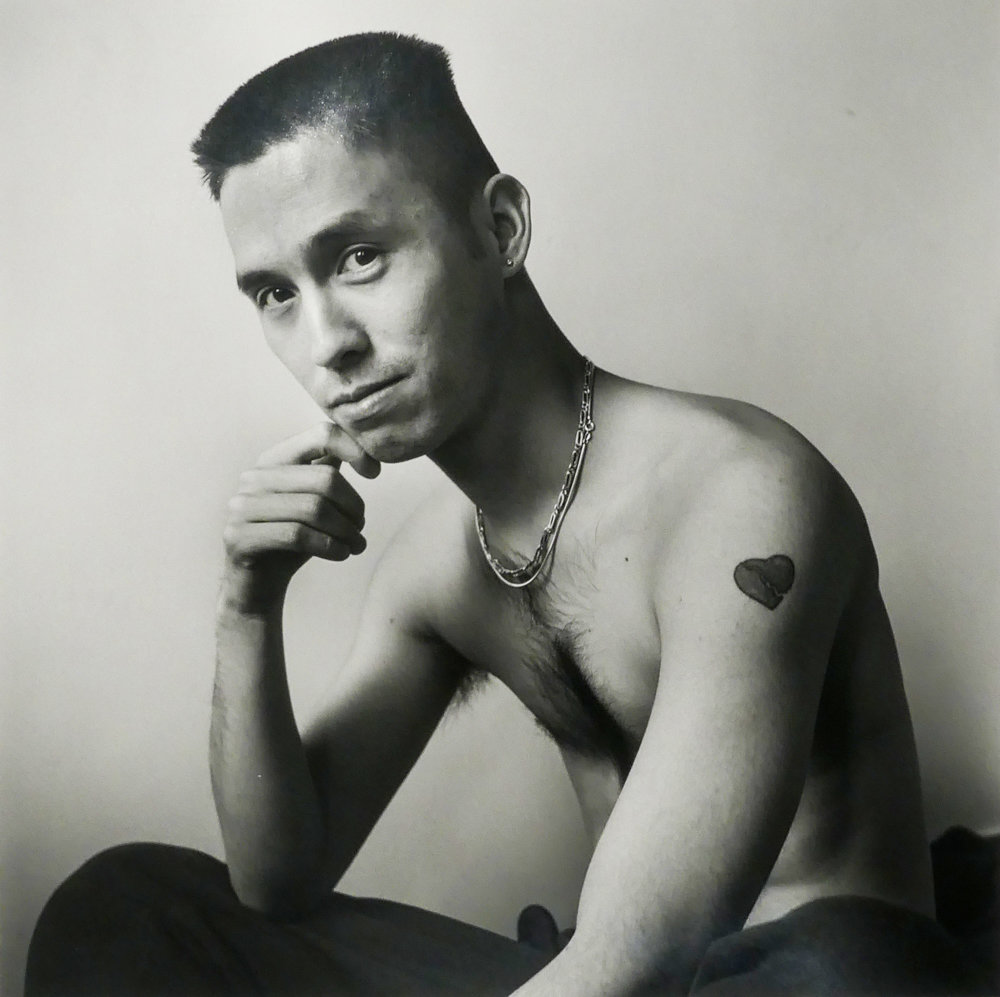

By photographing them in spaces where they were most comfortable, more of who they are comes through in the picture. With portraits done in a studio, emotional gravity and intimacy are communicated through the expression of the person being photographed. In the context of a writer’s home, as in the case of Klein and hundreds of others, more is communicated through the person and the space itself. These kinds of portraits lend themselves to greater emotional depth and complexity. They are more personal.

Giard started the project in 1985, and kept working on it until his death in 2002. It was initially published as a book — “Particular Voices: Portraits of Gay and Lesbian Writers” — in 1997. The Daniel Cooney exhibition arrives 50 years after the Stonewall riots, a series of demonstrations by the gay community following a police raid on the storied Stonewall Inn that many say marked the start of the gay rights movement.

In thinking about ways to commemorate the riots, curator Daniel Cooney did not want to show something too direct.

“My first thought was to do a group show about Stonewall,” Cooney said.

He quickly realized, however, that other institutions would likely do that, as there is a wealth of photos from the riots themselves, and elsewhere, that are more representational of the start of the movement.

“Particular Voices,” however, offers another way in. It shows a community of writers, artists and activists, and a world made possible — at least in part — by the Stonewall riots. Those not-so-peaceful demonstrations opened the floodgates, sparking a movement that has worked toward equality and freedom — freedom to live, freedom to love, freedom to exist.

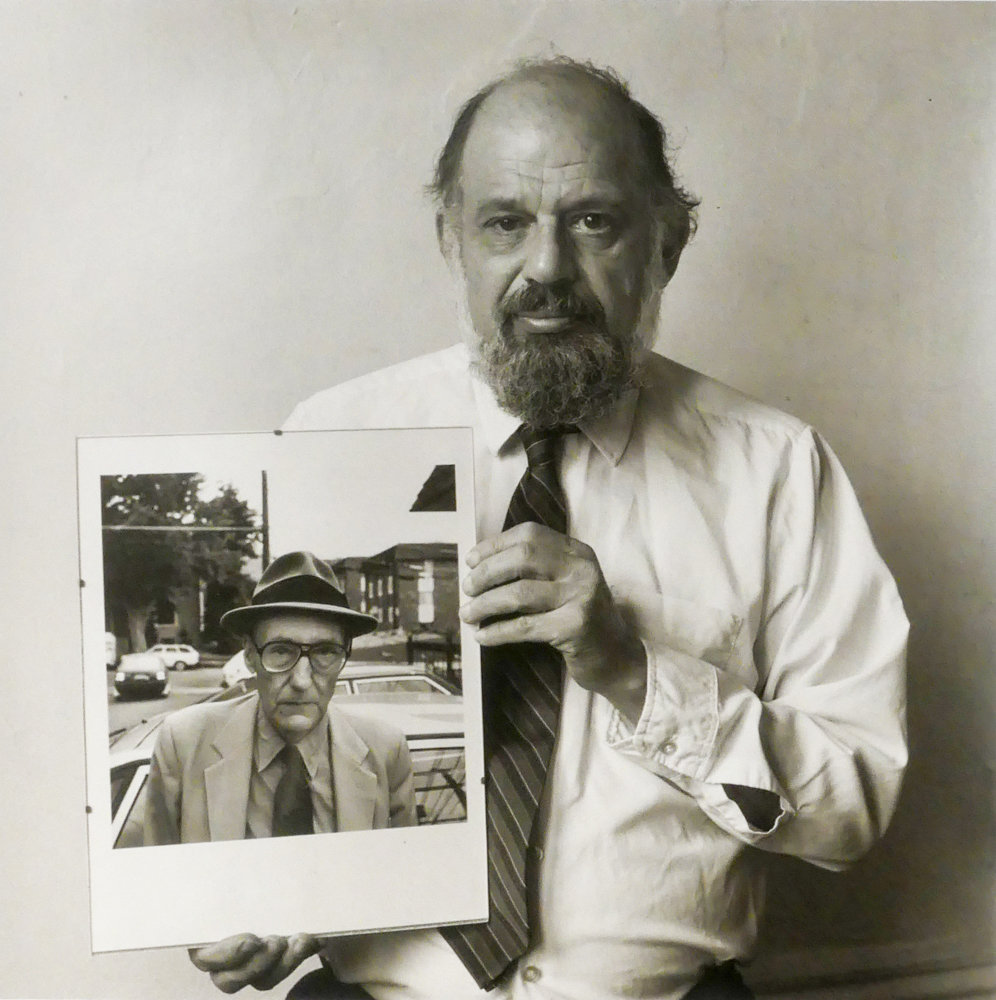

The writers Giard photographed run the gamut from the niche and esoteric, to names that jump off the page — like Allen Ginsberg, Adrienne Rich and Larry Kramer. The curatorial process was an education for Cooney, who didn’t know most of the writers, but was delighted by the discoveries he made.

“They were writing things that were really monumental,” he said.

“Particular Voices” is evidence of Giard’s commitment to his craft and to the community he photographed. This project took him all over the country, and as his partner Silin remembers, Giard plotted out byzantine travel routes, as he had neither a car nor a driver’s license. He worked without funding — and often without recognition.

“That is an extraordinarily important legacy for people who want to do work that isn’t immediately recognized,” Silin said.

History isn’t only written by the winners. It’s also written by those who realize that if they don’t do it, no one else will. Armed with a Rollei camera and rolls of black-and-white film, Giard was one of those people.

Over the course of nearly 30 years, he created a living historical document of LGBTQ writers, artists and activists of a certain era, many of whom have since died.

“It would be nice if in another hundred years people knew about these people still,” Cooney said.

Their memory lives on in their work. And in Giard’s portraits of them.

“We have to keep it alive,” Cooney said.