Even insurance doesn’t make health care accessible

In an ideal world, an individual probably has a handful of doctors. One for her eyes, her teeth. A gynecologist. And maybe a specialist or two depending on disabilities or chronic illnesses.

But connected to all those doctors is a primary care physician, the first point of contact for any sickness or illness. Someone who can prescribe medicines, therapies, and more doctor visits, if they’re necessary.

In the real world, that’s not quite the case. Especially without health insurance, or with restrictive insurance. Adding just one primary care doctor to a community of 10,000 people reduces death rates by more than 5 percent, according to Dr. Sarah Nosal, the chief medical information officer at the Institute for Family Health.

“We do know that when individuals and states and regions utilize regular primary care providers, there are less hospitalizations, less ER utilization, (and) cost of care goes down,” she said.

There are several reasons for that. Particularly in communities of color, people are at the mercy of “social determinants of health,” Nosal said, like access to resources, healthy food, financial security and even air quality. That often increases the rates of chronic illnesses, which without treatment, can degrade an individual’s overall health over time.

Nosal, who works at the Urban Horizons Family Health Center on East 168th Street, sees patients who have gone years without a regular physician visit. Some are diagnosed with advanced cancers that may have been caught earlier with regular screenings. Some, without an established relationship with a doctor, went years without vaccines for measles, even as the disease swept through the city in the time before the coronavirus pandemic.

The Institute for Family Health provides medical care for people with or without insurance and those who may not be able to pay for medical care with other providers.

“All of us see people who are uninsured,” said Maxine Golub, a senior vice president at the institute. “It does require us to put people on a sliding fee scale and send them a bill, but … we don’t send people to collections. We continue to see you even if you haven’t paid your bill in forever.”

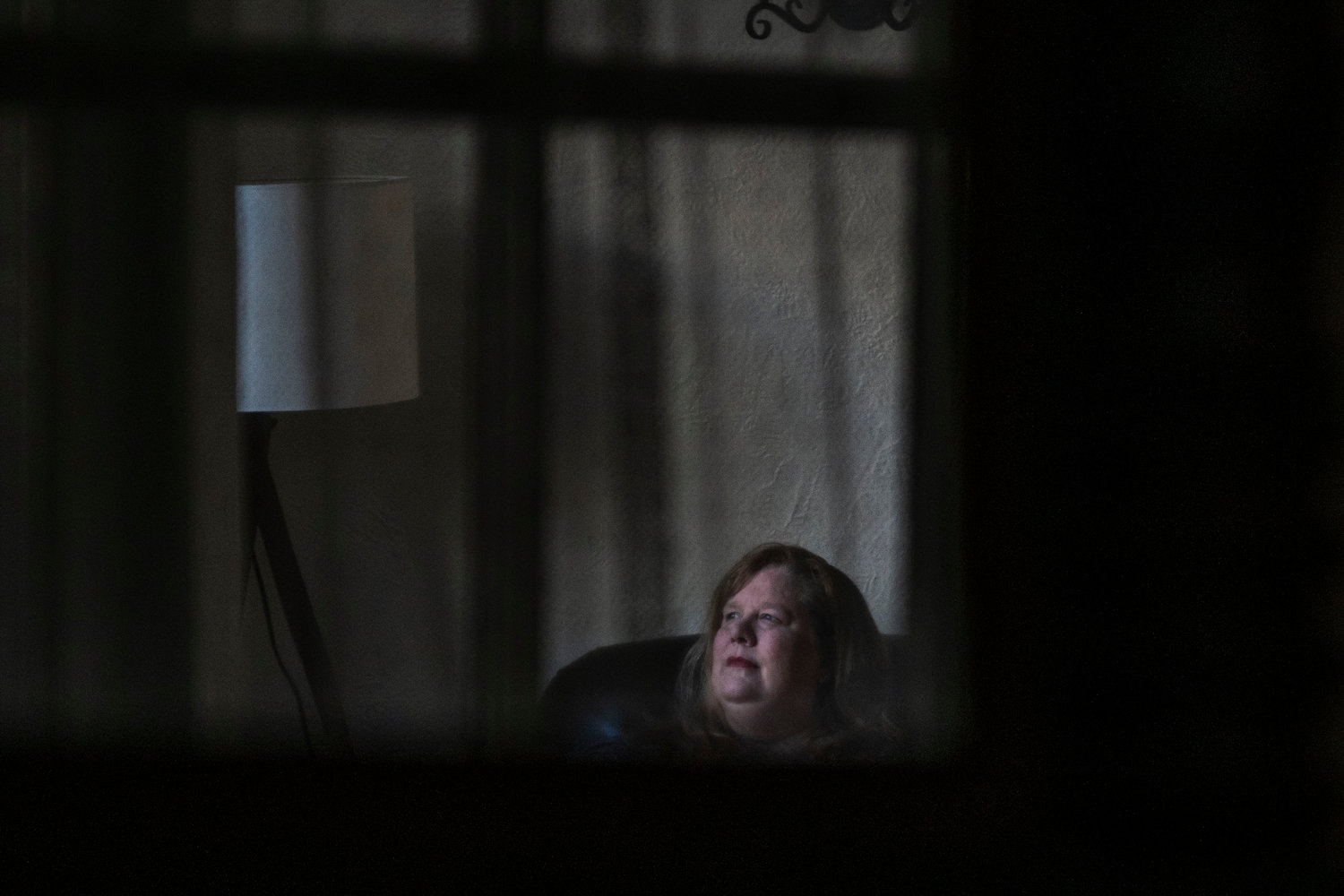

But while insurance is always helpful, it isn’t everything. Martha Ketro Fisher found that out the hard way one night when her teen son needed a doctor.

He had been feeling sick all day, she said, and then felt severe pain in his stomach.

Sam Fisher is usually pretty stoic, according to his mother, so seeing him in pain was particularly scary.

Martha thought he might have appendicitis, meaning he needed to go to the hospital immediately. But before they could set off, she had to figure out what would be covered by their family insurance plan.

“Weirdly enough, I was afraid of going and having it not be appendicitis,” she said. “So then us being charged for the whole ER visit. Because, again, it feels like roulette, like you’re not sure of the rules ever — will you be approved or will you not.”

Martha called the hospital’s after-hours line, and a nurse confirmed they’d have to come in to diagnose appendicitis. Her insurance card had a number to call for coverage concerns, but no one answered — it was an endless cycle of being redirected with no human conversation.

“At this point my son was literally writhing in pain, and saying, ‘Can’t we go, can’t we go?” Martha said. “And I’m like, ‘Sam, we’re going to go as soon as we can. We’re going to go, we just have to make sure it’s covered.’ And I was so upset, as a mom, how much he was in pain and I was still trying to make sure this wasn’t going to bankrupt us.”

Eventually, they piled into the car and drove from their Riverdale home to Mount Sinai West, the same hospital where Sam was born. After a series of tests, they were sent home with a $3,000 bill. Insurance paid for half of it, but the Fishers were still left with $1,400 — more than their monthly premium.

“What the hospital was willing to do, and I’m glad they were, was we could pay it off $100 a month,” she said. “So, the hospital did let us do that.”

People without insurance sometimes wait until their situation is dire to seek help — going to the emergency room or urgent care only once they’re very sick because they can’t afford care. But even with insurance, the threat of costly medical bills can keep people at home, something that was particularly apparent to Nosal during the worst of the pandemic.

“Some of the statistics that are really interesting and heartbreaking in the city is how many people died at home,” the doctor said. “The rate is much higher than it would have been. We can’t say those were COVID or not related deaths, but we know that many more people died at home than usual.”

Doctors at the institute regularly checked in with their COVID-19 patients via telemedicine, checking in on their symptoms and letting them know when they needed to come for in-person medical care.

The Fisher family all have what are typically considered pre-existing medical conditions, and before the Affordable Care Act, wouldn’t have been able to purchase the private insurance that covers them now. Martha said she wishes New York would pass its own universal health care bill to cover her family and people like them no matter what happens to the federal bill.

“That said, I’m glad that we can even have insurance,” Martha said. “Which is a pathetic thing to be grateful for.”