MTA’s worst days are behind us

When Andy Byford took over as president of the New York City Transit Authority a year ago, he declared the system responsible for moving millions of people around the city “in crisis.”

Before he could even move into his office, Gov. Andrew Cuomo declared a state of emergency for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, after what many declared was the “Summer of Hell” in 2017. It was a time when train breakdowns trap-ped people underground, and even when subways were moving, there were excessive delays and daily service interruptions.

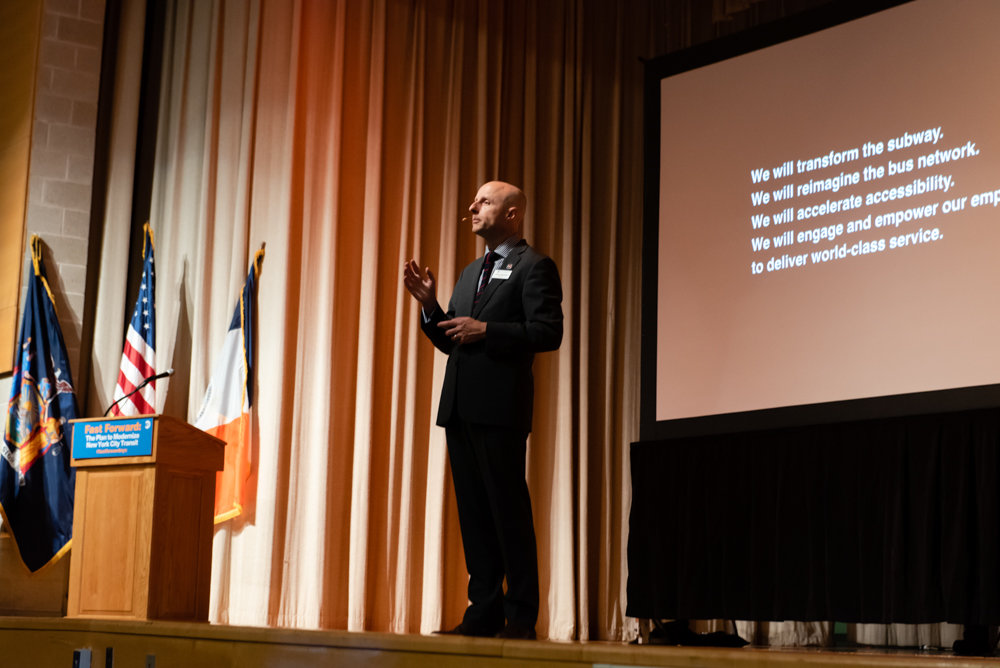

Two years later, it finally feels like the MTA is now emerging from those troubled times, said Byford, who visited IN-Tech Academy in Marble Hill last week to provide a Bronx-centric update on his plans to modernize the city’s mass transit system. At least to him, it’s now a “capable” system that has the potential to deliver better service to straphangers with some badly needed changes.

When he took the MTA position, Byford prioritized problems based on how immediately they needed to be addressed. The first? Reinvent the city’s subway system.

“Even before we get into the modernization of the transit system, every day we carry 5.7 million people,” he said.

Service is improving, despite major disruptions like the one that halted nearly all numbered lines on July 19. January’s service was 76.6 percent on-time, a dramatic increase over the 58 percent on-time rate the previous year.

Many stations need to be renovated. Crews have used late nights and weekends to complete a lot of track work, including signal, track bed and drain replacement.

“It’s disruptive,” Byford said, “but it will be worth it.”

The biggest leap forward for the subway system would be to implement communications-based train control, which already exists on the 7 line in Queens and the L line in Brooklyn. Right now, the subway operates on a traditional fixed block system, where trains must maintain a certain distance from each other using line-sight signals.

“The train in the back could only move forward when the signal allows it to, and this maintains a fixed distance between two trains,” Byford said.

The more trains on the tracks, the less safe and reliable fixed block systems are, he said. Communications-based control allows the trains to communicate with each other without necessarily having to see each other.

“As train number one moves forward,” Byford said, “train number two and train number three can move up.”

The system is more reliable, efficient and it “means you can run way more trains.”

Where fixed blocked system trains run at about 70 percent punctuality, the 7 and L trains are more than 90 percent, Byford said. More trains took the route, and their respective travel times decreased.

But modernizing the rest of the subway system is a daunting task. It took seven years to install the new system on just two train lines.

MTA officials believe they can make the switch within the next decade by keeping it simple.

“Buy off-the-shelf, proven products, minimize customization, don’t complicate the interfaces,” Byford said. “Take advantage of weekend closures.”

Another priority is reimagining the bus system serving 2.7 million riders daily. Bus redesign is especially needed in the Bronx where subway service falls short.

“People are leaving the bus system in droves,” Byford said. “Why?”

It’s because buses are stuck in traffic, the more than 300 city bus routes are outdated, and riders feel their voices aren’t heard.

The MTA is looking for rider input for its ongoing Bronx bus system redesign. Do riders want more direct routes and more frequent buses? Or longer routes that are less frequent but serves more destinations?

Do they want fewer stops and a longer walk to keep buses moving? Or keep the distance between them short for accessibility?

Accessibility has been a problem for far too long, Byford said. Only a quarter of the MTA’s train stations are accessible to people with disabilities and mobility issues. The MTA must “push forward with accessibility as quickly as possible” because it’s the “right thing to do.”

“Just 36 more, scientifically located, filling in the gaps,” Byford said. “Within five years, we can get you no more than two stops from an accessible station anywhere on the network.”

In the second phase of work, the MTA plans accessibility modifications to another 130 stations, geared toward significantly increasing accessibility citywide.

Third priority is to “push forward with accessibility as quickly as possible.”

“We can’t be proud of our transit system when a whole swath (are) excluded from it,” Byford said. “We’ve got to bite the bullet and make the whole system accessible.”