Pearl's brain is working hard, even after death

Late Spuyten Duyvil resident participated in study researching Alzheimer's disease, dementi

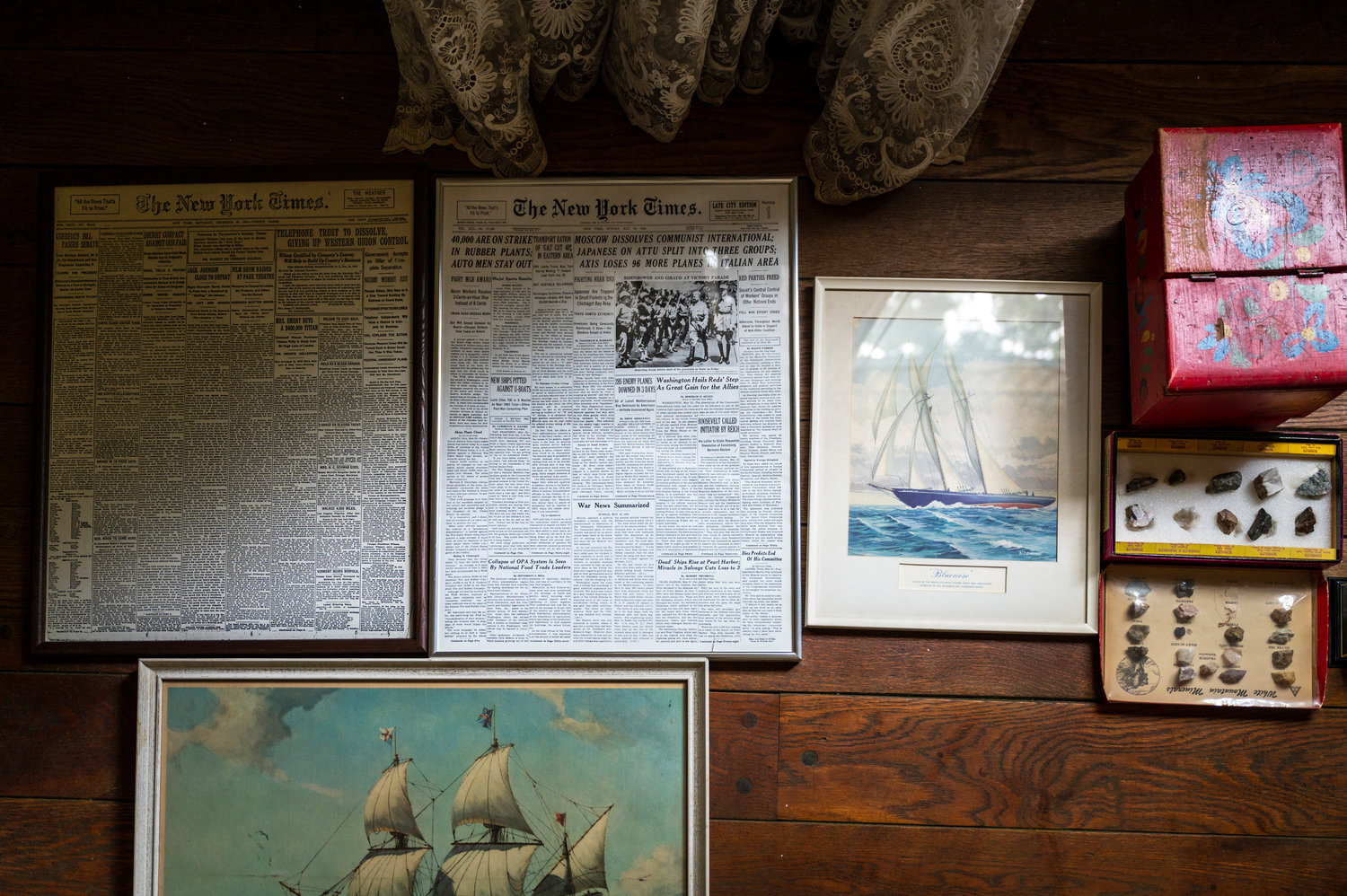

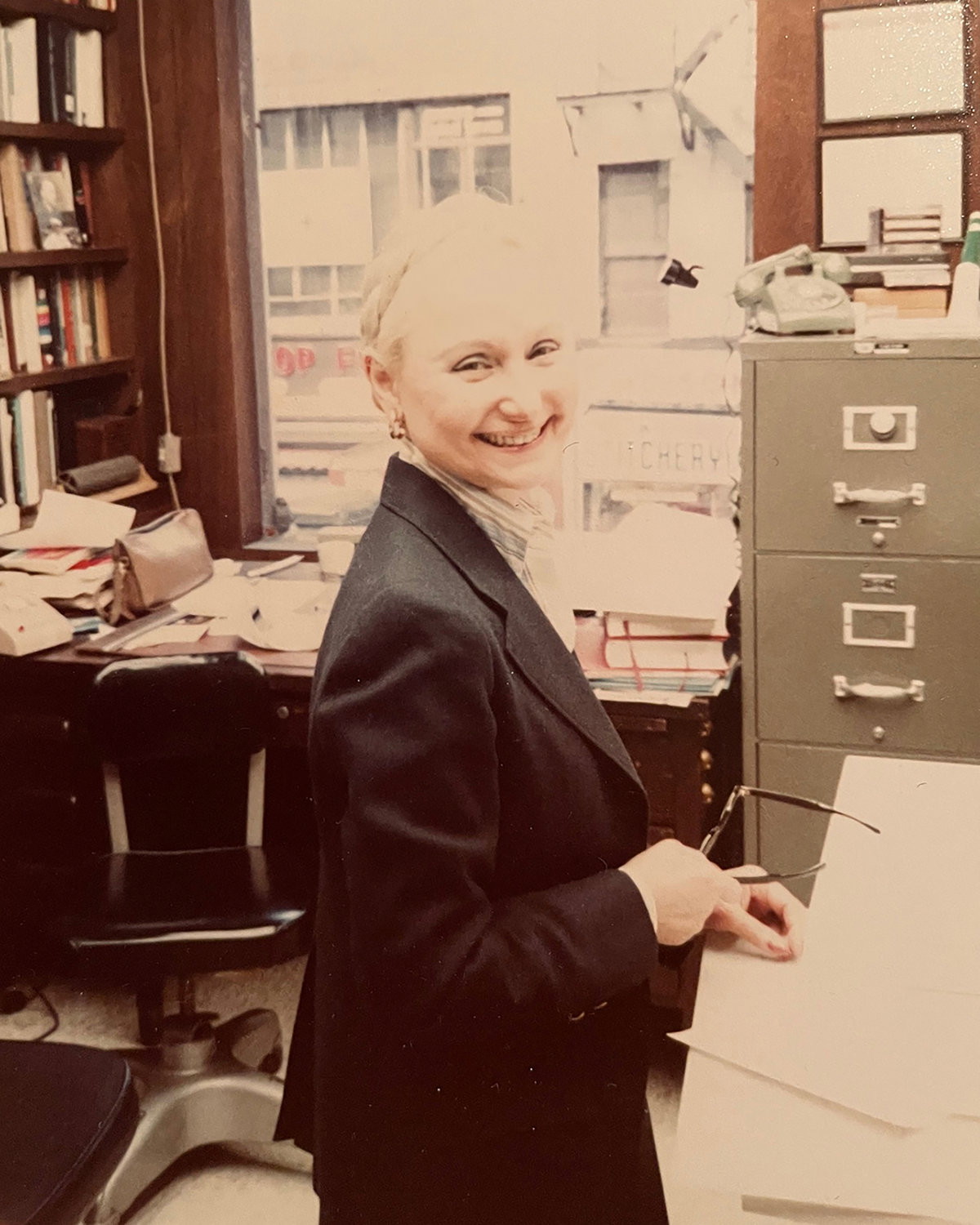

For decades, questioned document examiner Pearl Tytell used her hyper-specific skillset to expose fraudsters of all kinds.

Among the longtime Spuyten Duyvil resident’s greatest accomplishments were proving Eugenia Smith could not be the Grand Duchess Anastasia Romanov — the daughter of Russian emperor Nicolas II — through a close examination of Smith’s handwriting. And working as the main document examiner in the U.S. government’s case that convicted the Rev. Sun Myung Moon of conspiracy and tax fraud.

The community lost Pearl this past September at 104. But even in death, Pearl’s mind is still having a major impact on those around here — albeit in a very different way.

Pearl joined an aging study nearly two decades ago conducted by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in Morris Park in researchers’ efforts to better understand diseases like Alzheimer’s and dementia. According to daughter Pamela Tytell, Pearl joined the study after watching her husband’s rapid mental decline from Alzheimer’s disease.

“We started to notice changes in his behavior, such as being very aggressive and using swear words, which he would never use,” Pamela said. “Also, forgetting things. He was, for example, opening an envelope — throwing out the contents — and keeping the envelope. Or being on the telephone, putting it down, and then be doing something else and (would) forget that he had somebody on the telephone.”

When her father was diagnosed, Pamela’s mother was shocked to learn there were no treatment and very little research. That’s because the best way to study ailments like this is by performing brain autopsies.

So, in addition to joining the study, Pearl volunteered to donate her brain once she died — a decision that perplexed her children at the time.

“The neurologist said, ‘Look, if you’re very interested, you can be part of the program and donate your brain,’” Pamela recalled. “And my brother and I were surprised, and a little bit in shock. And (my mother) said, ‘Look, it’s the only way to advance research, and I’m going to be part of the study. It’s my brain, I’ll do what I want with it when I die.’”

What Pearl and many others do in making such a donation is more important than others may realize, says Richard Lipton, a neurologist who’s overseen the program since 1992.

“The reason brain evaluation is important is because adults with cognitive impairment have problems in their brain,” Lipton said. “And by doing autopsies, we can figure out the precise causes of the problems, the mechanisms of decline. And that sets us up to better understand how to diagnose and how to treat in the future.”

Studying the brain is also essential for understanding what brain diseases an individual might have in addition to Alzheimer’s.

“The question studying the brain answers is Alzheimer’s and what else?” Lipton said. “Alzheimer’s and strokes? Alzheimer’s and hippocampal sclerosis? Alzheimer’s and Lewy body dementia? And understanding what’s going on in the brain that contributes to cognitive decline is very important because the interventions that we do to reduce the rate of cognitive decline — or prevent cognitive decline — depends on the cause of cognitive decline.”

While many may worry how brain donations might affect burial arrangements, its actually done in a way where it doesn’t change the body’s appearance, Pamela said. They do this by removing the brain through the soft tissue in the back of the skull, which makes it possible to still have open-casket funerals and wakes.

After the brain is removed, researchers freeze half of it, placing the rest in formaldehyde for two weeks. Then it gets sent to research facilities at various hospitals around the world.

Researchers give the brain a tracking number, Pamela said, so she and other family members can follow the research process.

Although Pamela knows her mother was probably too high-functioning at the time of her death to have had Alzheimer’s, she’s curious to know what caused her short-term memory loss. The pathology report, which Tytell was supposed to get a few weeks after researchers started studying Pearl’s brain, should reveal whether her mother had early-onset dementia, or was mostly suffering from mini-strokes.

But the aging study involves much more than just brain donations, Lipton said. People can still participate without making such a donation. Instead, researchers measure several health metrics to closely track physicals state while people age. This includes measuring cognition, drawing blood, looking at genetics, and monitoring sleep quality.

Researchers also regularly test participants’ short- and long-term memories to see if they have symptoms of Alzheimer’s or other forms of dementia.

“We collect a tremendous amount of data,” Lipton said. “I think most people participating in our studies genuinely enjoy being in the study.”

However, participants know being in the study is more about helping the advancement of research than improving their own health.

“Because they’re contributing to the science that will lead to the next generation of therapeutics, but possibly not the treatments that will directly benefit them,” Lipton said. “So, we’re incredibly grateful for the support the Bronx community has given us for all the years we’ve been doing these studies. And how generous they are with their time, and their willingness to let us learn about them in ways that will help other people.”