Refocusing from the virus to finding your next meal

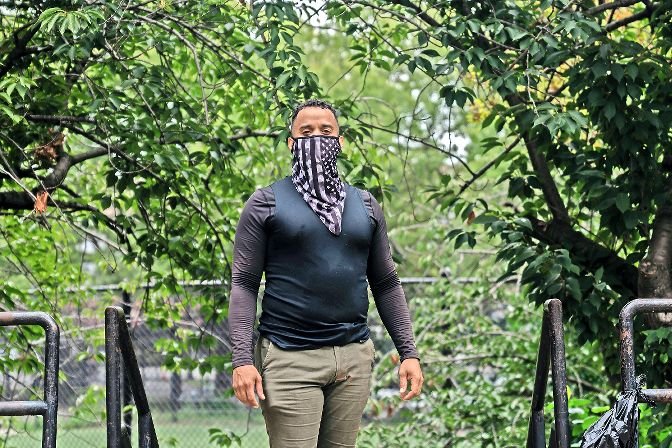

Not having enough good, healthy food to eat isn’t a foreign concept to William Littleton. In his job as the development director at Kingsbridge Heights Community Center, Littleton sees as many as 20 families every week without reliable access to food. He makes sure they don’t go hungry by inviting them to the center’s food pantry.

But as the year goes on and the coronavirus pandemic continues, more people are relying on KHCC’s wares — to the point where it’s no longer 20 families a week, but some 200 families. Per day.

While the city’s positive test rate remains stable, many in this part of the Bronx are still feeling the after-effects of its peak. Many city workers were furloughed, or lost their jobs altogether. And finding a steady job in the middle of an economic recession is no easy task.

That uncertainty of employment therefore led to another uncertainty: Could those facing unemployment put food on the table for their families?

Many community mainstays saw the growing hunger in the borough, and sought to address the issue as quickly and effectively as they could. And from that, the Northwest Bronx Food Justice Project was formed.

Sponsored by RSS-Riverdale Senior Services, and funded in part by Bon Secours Mercy Health Foundation, the food justice project brings together community centers and faith organizations throughout the region, including the Kingsbridge Heights Community Center, Outer Seed Shadow, St. Stephen’s United Methodist Church, the Marble Hill Community Center, and the Schervier Apartments.

One terms heard far too often in the Bronx is “food desert,” which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention define as “areas that lack access to affordable fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat milk and other foods that make up the range of a healthy diet.” To Andria Cassidy, a member of the project from RSS, this part of the borough might not be a food desert, but it certainly isn’t a food paradise either.

“It’s sort of a food swamp,” Cassidy said. “There’s loads of stores and loads of places to go (on) one side of the Major Deegan. But on the other side of the Major Deegan, where Kingsbridge Heights is, there’s virtually no shopping.”

KHCC runs a number of programs to help in that regard, but Littleton estimates its food pantry is the largest of its programs. He says while the food project was in the works before the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, the virus’ arrival in New York City all but necessitated its immediate implementation.

“We’ve worked to identify the needs of the community, and obviously the largest need that we identified — before COVID hit — was food insecurity,” Littleton said. “We can say that exacerbated because of COVID, hence the real rallying cry for us to support each other and make sure that we have the resources to support our community.”

To Cassidy, the project has a two-fold goal.

“We had recognized and identified that there was a lot of misinformation on nutrition,” she said. “There are two intents of the project … improve nutrition literacy in a very culturally sensitive and respectful way, and to improve access to fresh food.”

Those different components are interlocked, Cassidy added. Simply having access to food doesn’t necessarily mean they have enough food, or even the right food.

“Food insecurity also includes eating bad food,” Cassidy said. “We were surprised to find out that people thought a Pepsi and potato chips were just fine … for breakfast.”

Malnutrition can occur in a number of ways, whether someone isn’t eating enough food altogether, or is eating too much unhealthy food.

“It contributes to higher rates of health issues, sickness, higher rates of people going to the doctor’s (or) going to the emergency room because of those sicknesses, and a much, much higher burden on the health system that we don’t need at the moment,” Littleton said. “When people don’t have a healthy, balanced diet, we know that … they’re less able to react to and fight off diseases or sicknesses.”

Deborah Johnson heads to St. Stephen’s emergency food pantry at West 228th Street on Wednesdays, distributing flyers and infographics about health-related topics. As the project nutritionist, Johnson wants people to know everything out there, from the health benefits of kale, to information about the virus that causes COVID-19, or anything in between.

The information she provides isn’t limited to distributing flyers once a week. Like the food the project distributes, information must also be accessible. And she’s gotten creative in the ways people can access what she has to provide.

Each week, the project releases a new video, some of which Johnson films in her own home. She often features seasonal food and recipes, like in a recent video tutorial on making healthy water popsicles for the hotter days of the summer. Many of the videos, flyers and infographics are also posted on the coalition’s social media pages.

Most of the nutritional education the coalition provides had to go online because of the coronavirus pandemic. And Johnson was willing to do whatever she could to make that possible, even if it meant learning how to make and edit videos for people to watch.

“The plan was to be in the community, to speak to people in-person (and) to do workshops in-person,” Johnson said.

“It was tough to pivot, but I think that this coalition, this group of folks, (is) passionate about the work. So it’s coming out in how we’re rallying together and doing whatever it takes.”

CORRECTION: Northwest Bronx Food Justice Project is working on creating a partnership with cable channel BronxNet, but such a partnership has yet to be formalized. A story in the Sept. 3 edition provided a different status for a potential partnership.