Shedding new light on NYPD complaints

Despite a judge’s order, details about allegations against various officers come to light. But will it create true transparency?

It’s been just a few weeks since state lawmakers repealed Section 50-a, a state law that kept police records confidential unless a court order declared otherwise, or the officer themselves allowed the records to be released.

That meant it was difficult for the public — or even public defenders and advocacy groups — to get a hold of details about police officer behavior, especially when interacting with those they are tasked to protect and serve.

But now, even in the midst of a rather heated court battle, that information is no longer being kept secret. ProPublica — taking advantage of the fact it wasn’t a party to those lawsuits and current injunction stopping the release of the data — published a database detailing complaints against nearly 4,000 officers.

These were complaints made to the Civilian Complaint Review Board, an independent oversight agency that is supposed to serve as a watchdog for the New York Police Department. The board consists of 13 members, chosen by the city council, the mayor and the police commissioner. While the board can make recommendations on disciplining officers they find to be operating outside of established protocol, final decisions on what happens to officers is generally left up to the police commissioner.

The work the board did generally remained secret, rarely any information publicly coming out of their investigations. But that changed with the ProPublica database, something other groups have been fighting in court to release after 50-a’s repeal.

The data only includes officers who have had at least one substantiated complaint made against them — meaning the review board investigated the case and found evidence that the event had occurred on at least one occasion.

At the 50th Precinct, 66 complaints were filed against 41 officers. Each complaint can have multiple allegations, these 66 complaints, for example, detailing more than 180 allegations.

Precinct-wide, 50 of those allegations were exonerated, 64 were substantiated, and 70 were unsubstantiated. “Unsubstantiated” means that investigators couldn’t find enough evidence to prove the incident in the complaint happened. “Substantiated” means investigators could prove it and that rules were violated. “Exonerated” simply means that an officer did do what they were accused of, but that it didn’t violate any NYPD rules.

Capt. Emilio Melendez, who heads the precinct, has 12 allegations himself over a 15-year period, although none of them were filed while he was with the 50th. In fact only one allegation — described in the database as being discourteous to a 27-year-old man in 2018 — was substantiated by the CCRB.

Most of Melendez’s complaints came in the early 2000s, when he was a lieutenant in Brooklyn’s 77th Precinct. Those complaints included back-to-back accusations of stopping or questioning Black men in their late 20s, with one also accusing him of performing a strip-search. Melendez was exonerated on each of those accusations, while the rest were either unsubstantiated or exonerated.

New York’s powerful police unions, including the Police Benevolent Association and Sergeants Benevolent Association, filed a lawsuit in the New York State Supreme Court seeking to block the release of CCRB complaints. The unions got at least a temporary injunction preventing the city, the CCRB and even the New York Civil Liberties Union from disclosing any of the data.

Union spokesman Hank Sheinkopf said releasing the data would “destroy the reputation and invade the privacy—and imperil the safety” of NYPD officers.

“This is not a challenge to the public right to know,” Sheinkopf said in a statement to the media last month. “This is not about transparency. We are defending privacy, integrity, and the unsullied reputations of thousands of hard-working public safety employees.”

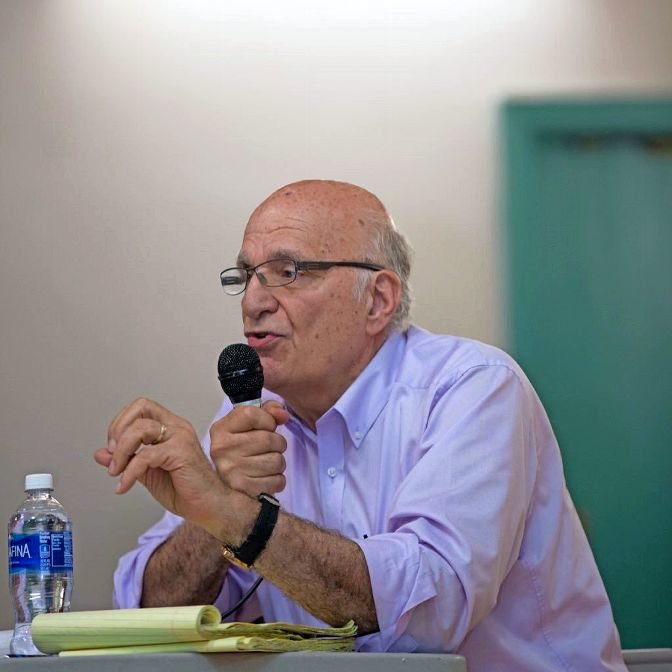

Robert Gangi, founder of the Police Reform Organizing Project, said that while releasing information was important, PROP and others knew enough about the NYPD.

“One of the judgements we’ve made is that we don’t need more information,” Gangi said. “Because we know how abusive and how racist policing is, and sometimes how violent it is. And how many ways police officers disregard and disrespect New Yorkers.”

Gangi pointed to a July 28 arrest apparently made by the NYPD warrant squad. Nearly a month after 18-year-old Nikki Stone had allegedly defaced police cameras, officers arrested her by finding her and pulling her into an unmarked minivan during a protest, chasing away people who tried to stop the arrest. Stone was released from custody early the next morning.

“On June 30, she engaged in vandalism,” Gangi said. “The way we think about that is, even if it’s true, she engaged in vandalism on June 30, (police) actions were violent. Inappropriate, maybe illegal.”

While many were shocked by the video, Gangi and others heavily involved in police activity said they weren’t surprised — people report that kind of police behavior to PROP and public defenders regularly.

ProPublica noted that in all cases — including those found to be unsubstantiated — the CCRB often relies on police to provide evidence, including body camera footage. According to a CCRB memo published by the outlet, as of late June, the board had not received footage from more than 1,000 requests.

The memo noted that withholding footage halts investigations.

It’s unclear whether any unsubstantiated cases at the 50th were lacking evidence, as the data does not specify a reason for conclusions rendered.

Some allegations from the precinct appear to stem from one police interaction — a 2016 complaint filed against officer Mayko Matos in regards to the arrest of a 36-year-old Hispanic man. The complaint accuses Matos of being discourteous as well as strip searching the arrestee and frisking him. Only the strip-search was classified as substantiated, while the rest — including physical force — were deemed unsubstantiated or even exonerated. Another officer, Sgt. William Butler, also is named in two allegations in the complaint.

No other details about the complaint were released.

Gangi said he hoped the data becoming widely available would spur people in power to take real action.

“The release of this information would be much more impressive and relevant if politicians in power, and editorial boards used it to make a strong case for dismissing the officers,” he said. “To dismiss officers who have engaged in abusive conduct.”