CUNY contract debate reveals larger adjunct struggle

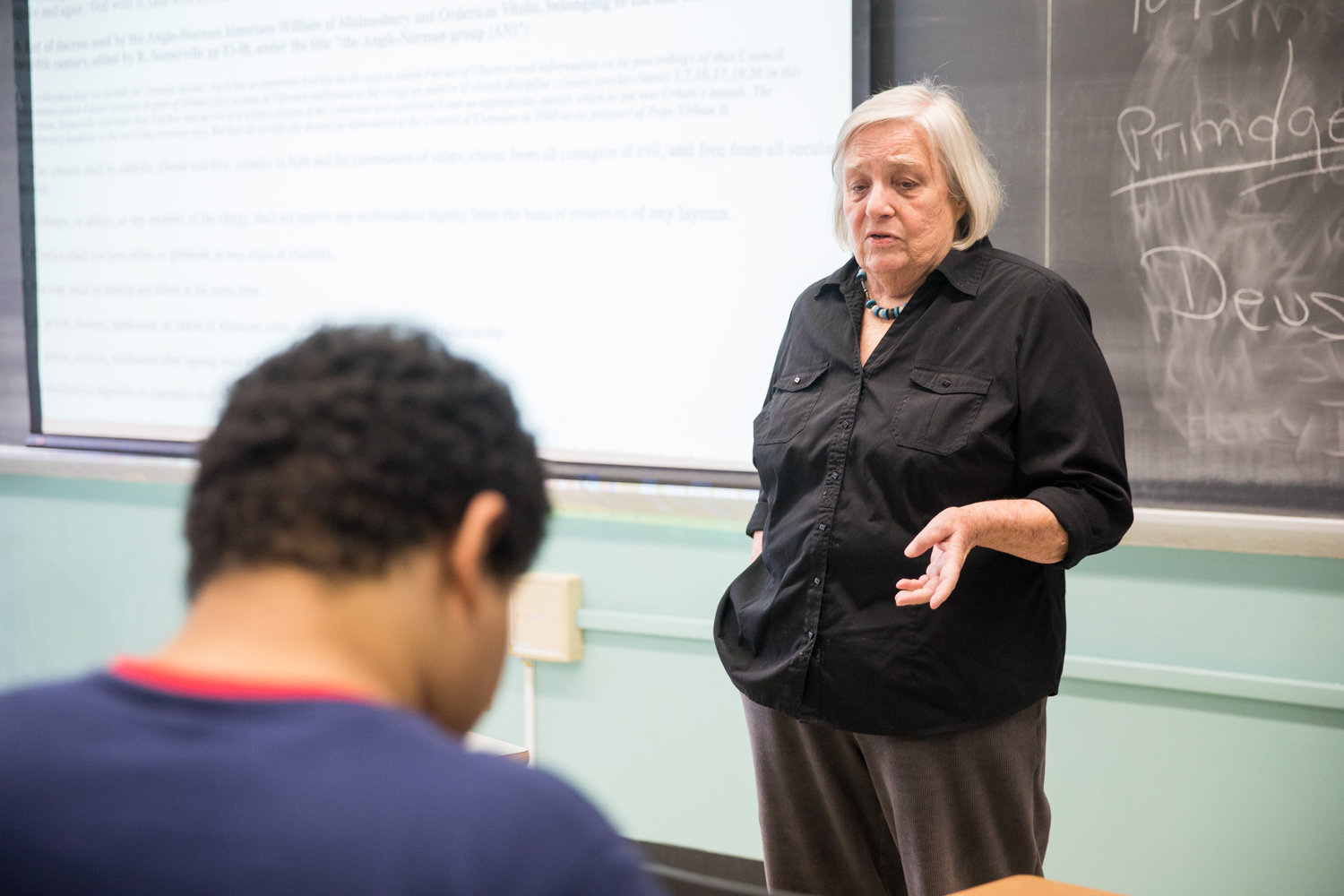

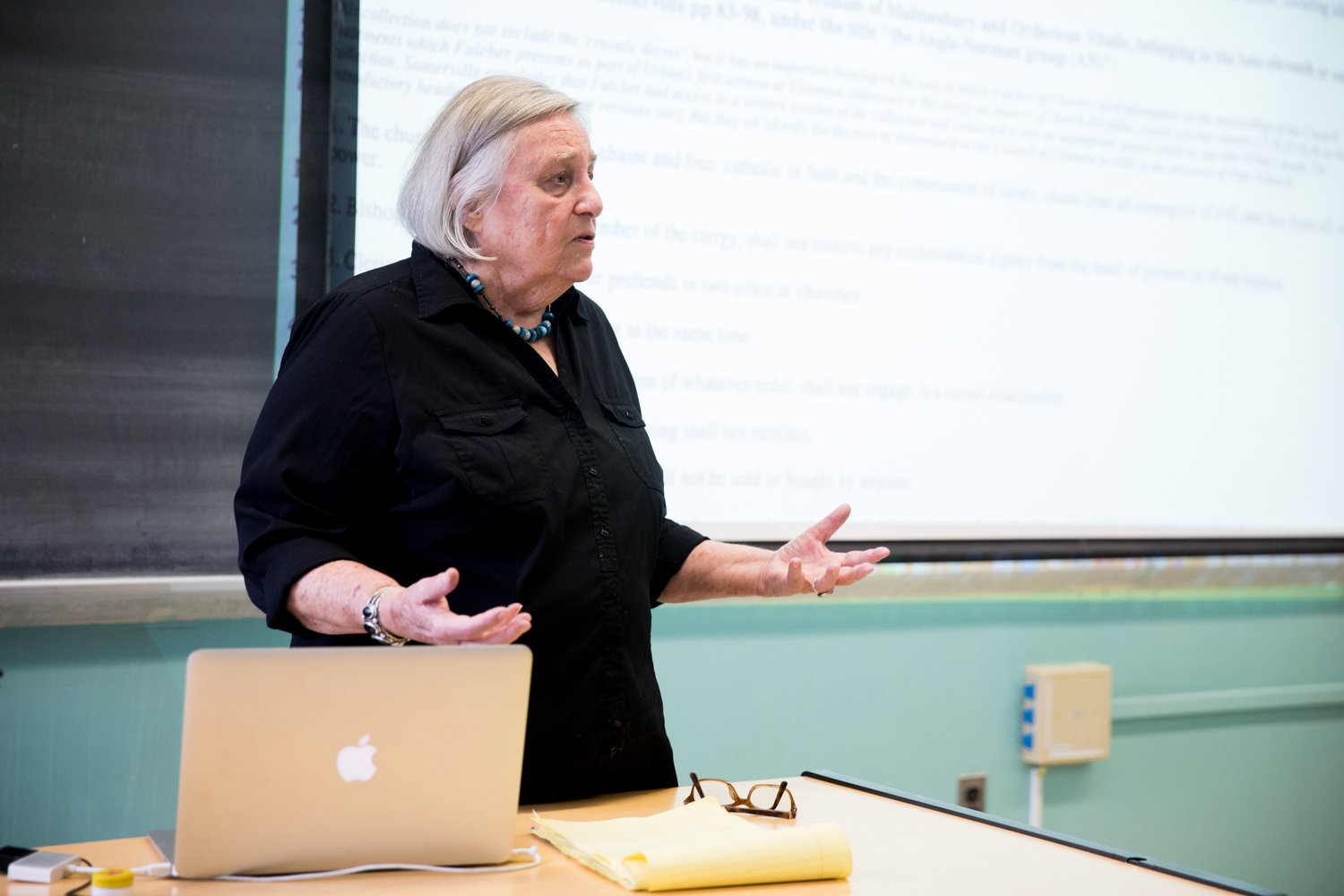

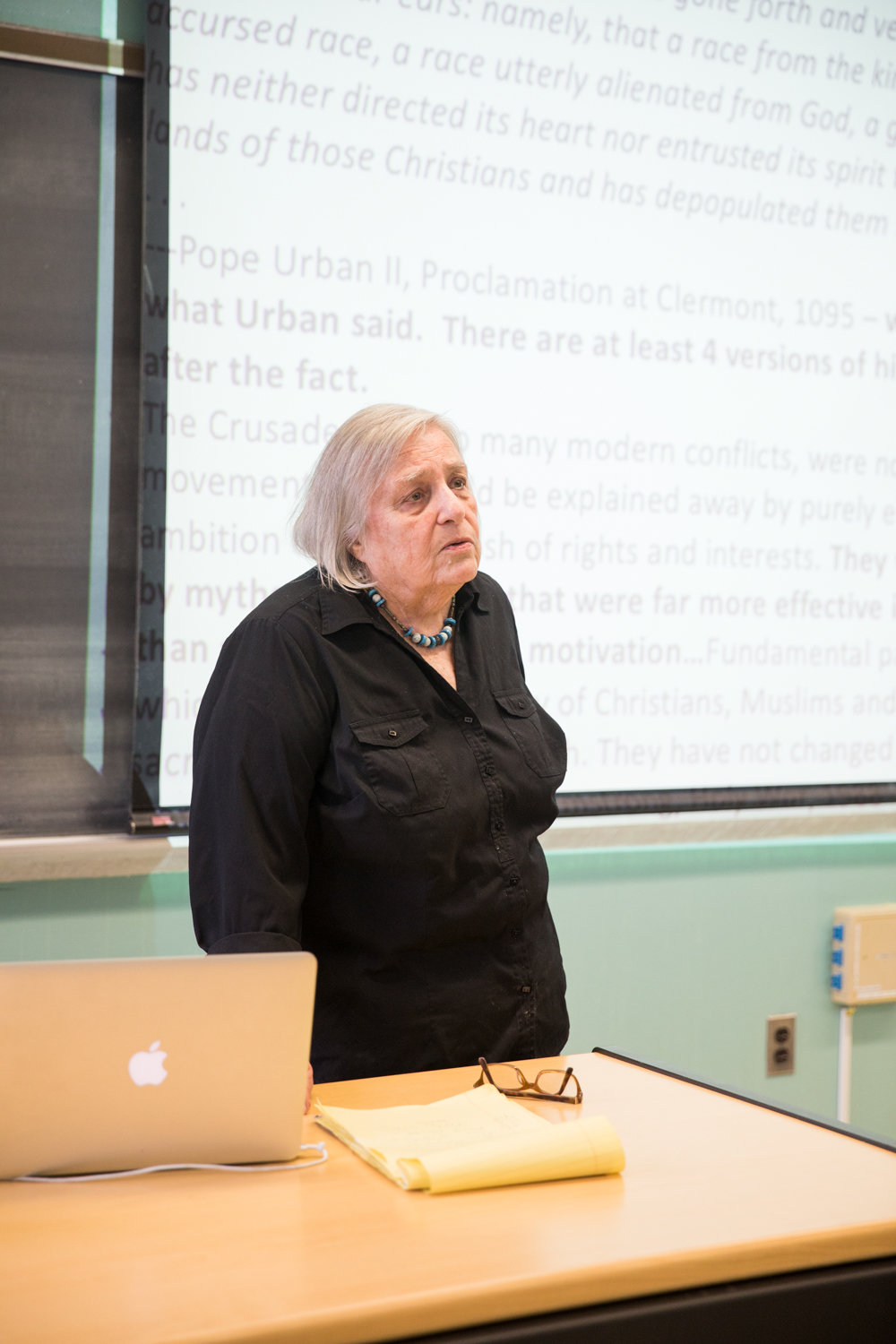

Diane Auslander barely scrapes by on the paychecks she gets for teaching at Lehman College.

One of City University of New York’s nearly 12,000 adjuncts, Auslander has a story that’s fairly common: She has two master’s degrees and a Ph.D. She would rather be a full-time professor, but adjuncts are rarely able to get on the tenure track, stuck instead as a sort of contracted teacher for the school, making $3,200 per course at the lowest level.

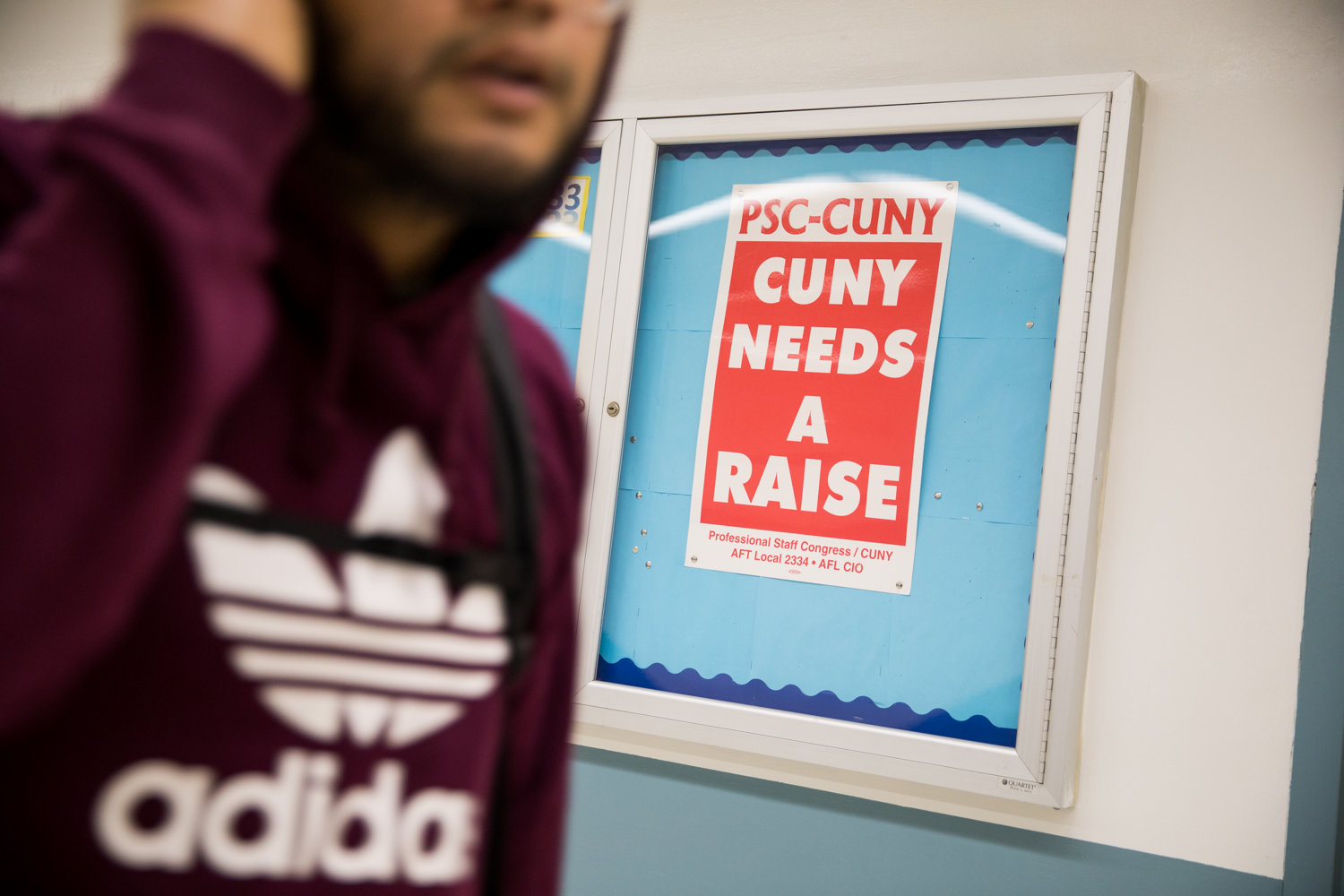

Adjunct professors have been the primary focus of CUNY’s faculty union, the Professional Staff Congress, which recently put the final touches on a new contract with schools, leaving it up to union rank-and-file to cast a yea or nay vote.

The contract would raise adjunct salaries across the board, beginning at $5,500 per class by 2022, and gaining one paid office hour per class per week.

It’s the biggest breakthrough on adjunct pay the union has ever made, according to the congress’ website, and one of the better adjunct contracts across the state. It could have a tremendous impact on CUNY with its 300,000 students and 30,000 employees.

Auslander is ready to vote yes on the new contract. But others aren’t so convinced.

“If you’re not in a tenure track, and you’re not getting paid enough, it’s not equitable,” said Stuart Chen-Hayes, a full-time education professor at Lehman. He plans to vote against the contract.

“You don’t move up in the ranks, you don’t move up,” said Ruth Wangerin, an adjunct assistant professor in the anthropology department.

Wangerin is semi-retired, working at Lehman to supplement her pension from a past job. While she acknowledges the proposed contract would boost many of her fellow adjuncts, it doesn’t do enough for people like her, who have worked at Lehman for years, won’t receive any large raises, and still aren’t making much money.

It’s because of that Wangerin plans to vote “no.”

Groups like CUNY Struggle and 7KOrStrike say the raise isn’t enough to keep up with adjunct workloads and the cost of living in New York City. 7KOrStrike say the minimum raise should be $7,000 per course — reflected in the group’s name — and Chen-Hayes agrees $5,500 just won’t cut it.

“I don’t think that’s right,” Chen-Hayes said. “The bottom should be coming way up, even above $7,000. This harms everyone. It harms students, it harms adjuncts.”

The union wasn’t able to negotiate for everything they wanted, yet significant gains were still made, according to union president Barbara Bowen. The professionals congress is now much better positioned to negotiate higher wages and more gains the next time the collective bargaining agreement comes up for renewal.

“A three-credit course went from $3,200 to $5,500,” Bowen said. “It’s the biggest gain we have ever made in adjunct salaries. (It) really transformed the adjunct salary system. It’s the biggest raise in adjunct salaries across the country.”

There were more than simply raises at stake, however. Professors are pushing CUNY to return to being tuition-free, as it was until 1976.

Bowen campaigned for just that cause, and even rallied against tuition hikes. But CUNY is still significantly underfunded, she said, and moving to waive tuition just isn’t in the cards for now.

Another union concern is the Taylor Law. Formally the Public Employees Fair Employment Act, the law forces public organizations to negotiate with their employees to ensure fair conditions, among other things. It also codifies an inability for public employees to strike, meaning that CUNY employees and their union could be penalized for grabbing signs and heading out to march and chant.

Growing up in Chicago as the son of a public school teacher, Chen-Hayes said he was often walking the picket lines with his father. It was through those strikes — and more recently seen during this year’s teachers’ strike — that helps affect the large-scale change he and others want to see.

“It’s a basic labor right, it’s a basic human right and civil right,” Bowen said. “Workers should be able to withhold labor without that being illegal.”

When Chen-Hayes got his first gig as a full-time professor, he lived in New Rochelle while a friend who worked as an adjunct professor lived in his basement, unable to pay rent from her salary. In his eyes, that system hasn’t changed much today, and won’t improve in the near future with the current contract in front of them.

He agrees with Wangerin that the adjunct system must fundamentally change since it has come to represent overworked, poorly paid educators.

“I’m on a mission to regularize the adjunct faculty,” Wangerin said. “So there isn’t contingent faculty. I would like to be on a fractional line as a regular assistant professor, but half-time, that’s what I want. That’s what I want for everyone. Get them full-time if they want to, part-time if they want to.”

For Auslander who seems to have the most at stake, the contract is not everything she wanted, but she supports the raises. Voting “no,” in her opinion, could ultimately be more harmful for Auslander and other adjuncts.

“I didn’t like the contract when I first saw it, I was very disappointed in it,” Auslander said. But then she realized her initial expectations may have been “unrealistic,” and thinks voting “no” won’t be helpful in the long run.

“I’m living very much on the edge,” Auslander said, struggling to pay off medical expenses and student loans with her paychecks.

“This will help, my salary will go up. I have to wait to get the checks to see how noticeably it will go up. I don’t think it will be terribly noticeable, but every bit helps.”