Discovering the east without leaving the Bronx

It was thanks to her curiosity that Emily O’Leary brought the untold stories of Eastern Bloc artists to Riverdale.

Back in 2010, the associate curator at Derfner Judaica Museum + The Art Collection at the Hebrew Home at Riverdale was learning about its collection of 4,500 artworks that are housed across the facility.

O’Leary discovered a lithograph in the collection that caught her eye. She wanted to learn more about who the artist was, but when she looked at the digital database, it led her to a dead end.

“The artist field just said, ‘Russian,’” she said.

O’Leary suspected this dead end had something to do with a problem many museums have when it comes to transitioning from paper to digital databases, so she did more research to figure out who the artist was.

As she continued on this research journey, O’Leary felt like she had opened Pandora’s box when she found out the lithograph — along with other pieces she came across — were created by artists from the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc countries, a group of communist states in eastern and central Europe under Soviet control, during the Cold War.

“There was this whole story behind how we got this group of objects way back in the ‘70s,” she said.

Humble beginnings

That story stems from Jacob Reingold, the Hebrew Home’s late executive director and father of current facility head Dan Reingold, who created the facility’s Art Collection back in 1975. Early acquisitions came from various donors and members of the facility’s board.

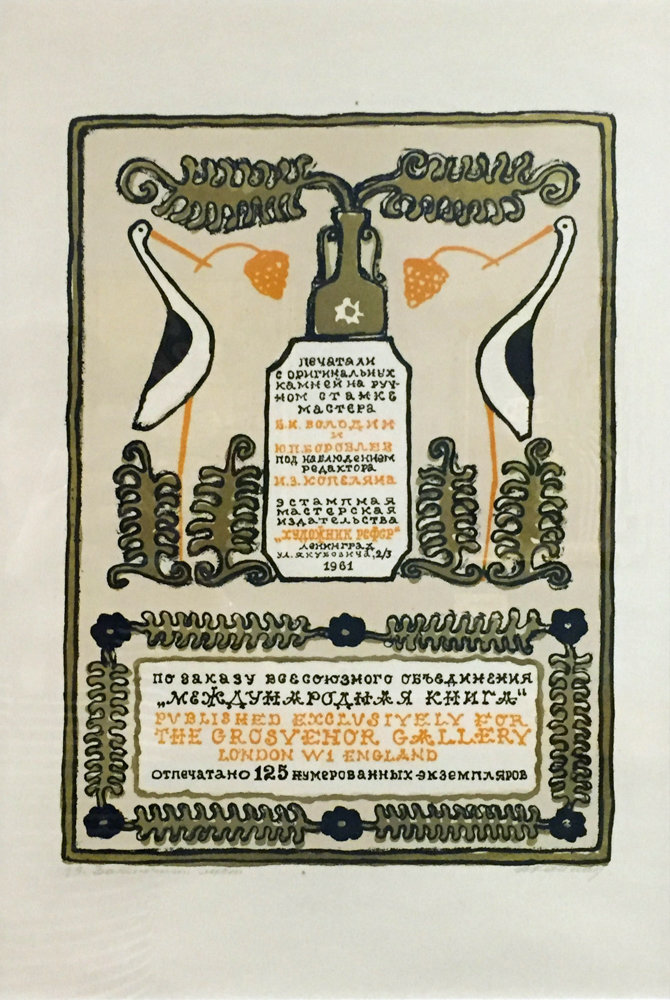

Many of the pieces O’Leary stumbled upon came from Eric Estorick, an art collector and dealer who ran the Grosvenor Gallery in London and exhibited artists from the Eastern Bloc, exposing western culture to these unknown and underground names in the industry. Estorick’s father happened to live at the Hebrew Home for a bit in the 1970s.

Now, everything from O’Leary’s discovery is on display at the museum’s latest exhibition, “From the Eastern Bloc: Early Acquisitions from The Art Collection,” through Aug. 25. The show’s opening reception takes place May 19 beginning at 1:30 p.m.

The exhibition also coincides with the 10th anniversary of the museum’s move to its current space after being housed in what is now the Hebrew Home’s Riverwalk living community.

“Ten years have flown by, so we thought of different ways that we could highlight what we do here and what has been accomplished since we moved into the space (and) since we collected art,” O’Leary said. “This show just seemed like an interesting crossover with The Art Collection.”

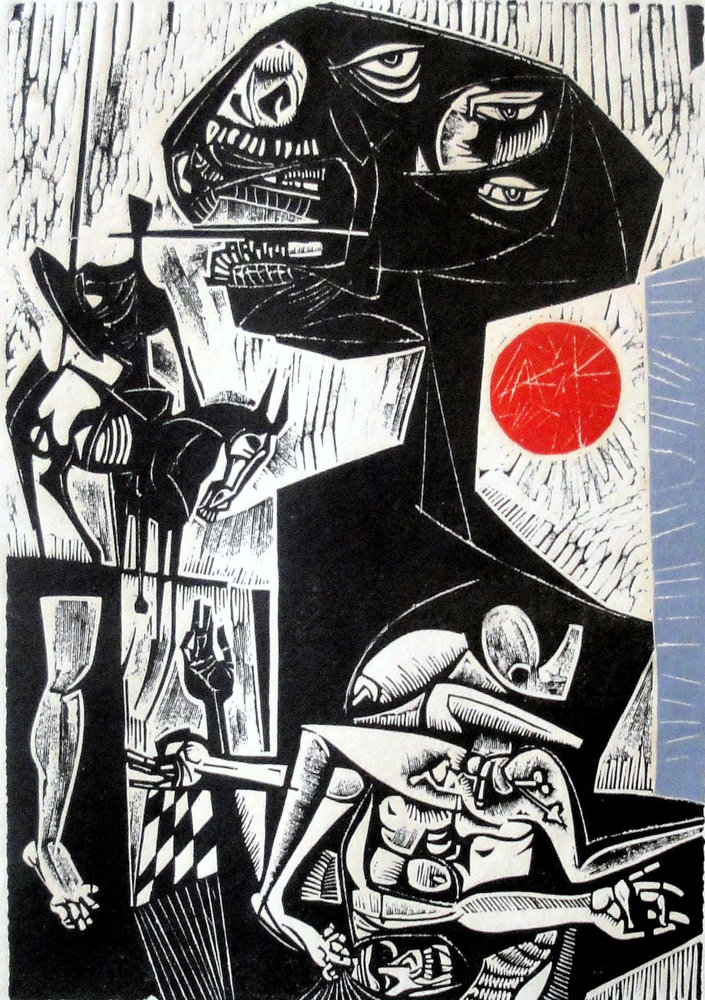

One of the notable pieces in the exhibition is work from Russian artist Oscar Rabin, a railroad foreman who painted what he saw on his way to work each day. His creations went against the norm of what the Soviet Union wanted its artists to produce, and he was eventually exiled to Paris in 1978.

“You had to be a member of the Artists’ Union (of the USSR) and you had to create work that fell in line with the style that was acceptable, known as socialist realism,” O’Leary said. “So anybody who worked outside those confines in style, or how they practiced art, was considered dissident depending on what it was.”

Celebrity status

“From the Eastern Bloc” also includes work from Mariam Aslamazian, an Armenian artist who some have called the “Armenian Frida Kahlo” based on aesthetic characteristics in her work.

While many of these artists are unfamiliar to people in the United States, many are essentially celebrities in their home countries.

O’Leary realized that during Women’s History Month in March when she shared an image of Aslamazian’s work to the museum’s Facebook page and tagged The Gallery of Mariam and Eranuhi Aslamazyan Sisters, an Armenian gallery dedicated to works Mariam and her sister produced.

“All of these people started liking it and it was this reaction of, ‘What is this museum that has Mariam Aslamazian in New York City?’” she said.

Having work from artists like Aslamazian and Rabin has “opened certain doors and connections,” O’Leary said. It’s allowed them to talk with relatives of artists who are still alive, giving them a chance to share works from their collection in places like the Slovak Republic embassy in Manhattan.

“Putting them into context of who these people were, who these artists were, who Eric Estorick was, with living memories and things has been really interesting,” O’Leary said.

Since the museum is one of the few to house works from artists in this particular era, “raising those profiles in the United States has been an interesting process,” she said.

“We’ve attracted attention, but also, I think a lot of these works continue to serve the intent that they were acquired with, which is to provide a stimulating environment for the residents.”

O’Leary encourages people who come to see the exhibition, especially if they might not know a lot about Cold War history. They won’t need that background.

“I would say come to the work, have your own reaction first, and then if you’re wondering what the historical context is, then you can go and research the artist,” she said. “It’s good to come to the show and just spend time with the work individually, not knowing what the background is and see how you feel about those individual artists and their work.”

Estorick thought the same thing, O’Leary says, because he relied on the “strength of each individual artwork to carry its own weight.”

“He literally just wanted people to come in, look at the work, be won over by it, and acquire it,” she said. “In terms of today, I think the same approach is equally as effective.”

Looking before you learn

Looking back at how much she’s learned about these artists in the last nine years, it’s been an exciting journey for O’Leary to learn about these pieces of artwork as well as all of their context and background information.

With that in mind, O’Leary hopes more people will be inspired to learn about Eastern Bloc artists after the exhibition.

“I do think that any art created in this period in the Eastern Bloc is not known,” she said. “There’s a lasting effect from the Cold War on artists who may have gone on to have very successful international careers had they not been locked in this oppressive environment.

“And I want more people in the western audience to know about them, to know about the amazing art that was being created in these countries during that period, because there’s some really significant artists.”

Especially when Eastern Bloc artists and artists from non-western countries are often overlooked from a historical perspective.

“I just really like the idea of introducing a part of art history that really is not known in the west, and it should be,” O’Leary said. “It’s an important part of the art history global canon.”