Electeds fighting for (and over) New York’s homeless

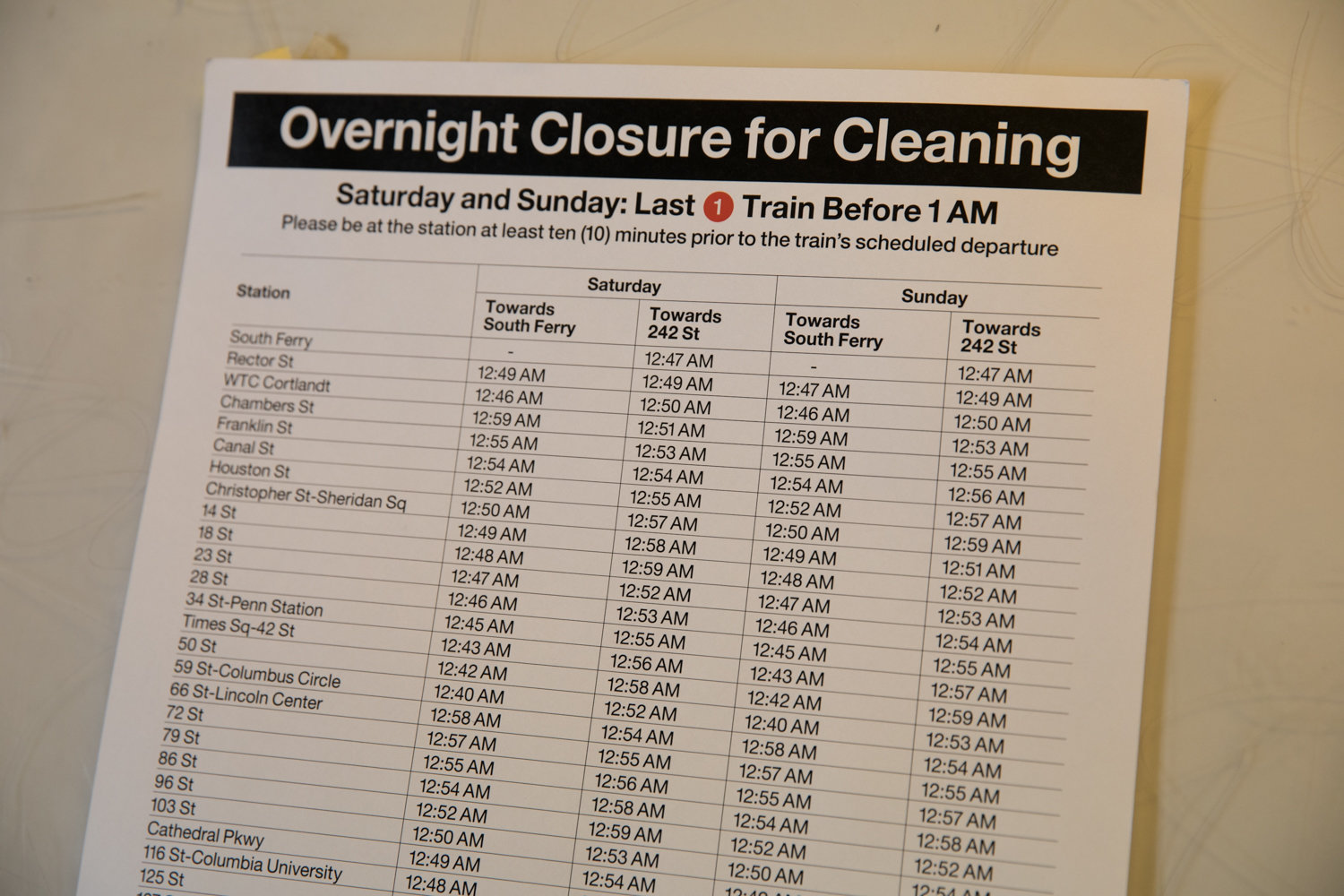

Every night since May 4, a swarm of police officers, city social workers and volunteers descend on subway stations that close just as the clock strikes 1 a.m., hoping to find people who need their help.

It’s a small army of people who have forsaken sleep in order to deliver as many homeless individuals into shelters as possible.

It’s all part of Mayor Bill de Blasio’s plan to abate homelessness while also disinfecting trains in the face of the coronavirus pandemic. The city’s social services department and city police are leading the effort, taking advantage of the nightly shutdown as a way to intervene with a population of people who make various subway cars their home when the sun goes down.

Between the start of the program May 4 through May 17, more than 600 people have accepted help in the form of either shelter or a hospital, city officials said. In one week alone, 181 homeless people found room in a shelter — and more than 60-percent of them were still in the shelter a week later.

“These numbers, they may seem to some like a small number in the context of New York City,” de Blasio said — especially since New York’s homeless population is said to exceed 4,000. Yet, this was major progress.

“When you see a hundred people in a week come in to (a) shelter and stay there, that’s actually a major step towards reducing permanent homelessness once and for all,” the mayor said, “and ending it once and for all.”

Not everyone who gets a ride from the subway to the shelter ultimately goes inside, however, according to social services commissioner Steven Banks. Many get to the shelter and decide, for whatever reasons, they’re not yet ready to get the help found on the other side of the doors.

“To have someone on a subway platform accept help and then when they arrive at the shelter door, make a determination that they don’t want that help that night, that is actually a step forward,” Banks said during a recent media briefing with de Blasio.

“The victory one night might simply be to get someone to say, ‘I’ll accept services and go to the entry point of the shelter.’ We’re not going to give up.”

But not everyone is quite so thrilled about the shift from subway cars to homeless shelters. Not because they don’t want to help people, but because they say the shelter system already is busting at the seams, housing close to 80,000 people. Some — like Assemblyman Jeffrey Dinowitz — have suggested the city use many of the hotel rooms left vacant by the pandemic. But that’s not something de Blasio was considering.

Hotels and motels were part of homeless “scatter sites” that were prominent mechanisms in fighting homelessness with administrations prior to de Blasio.

Since taking office himself, the mayor has shifted that approach to facilities that are all in one location, so that many of the services those trying to escape from homelessness are available to them on-site.

Plus, using hotels hasn’t always generated positive stories. An infant died in the Van Cortlandt Motel on Broadway and West 256th Street in October 2016.

The child and its mother were one of 30 homeless families who had just moved into the motel.

Not long after that, de Blasio publicly committed to eliminating the city’s use of hotels as shelters as part of a 128-page plan that redesigned the system into one that was more cluster-based, instead of scattered.

Today, many of the same elected officials in City Hall and Albany want to pressure the mayor into moving out of shelters and back into hotels — especially when many of them could use the income that would otherwise be absent, with vacant rooms.

“I think we have to look at it in the context of what arguably is the worst health crisis in the century,” Dinowitz said. “There’s no tourism, so on the one hand, I do think that we have to take measures to make sure we keep people safe, but that it (also) doesn’t turn into a long-term situation.”

In light of extenuating circumstances during the COVID-19 pandemic, Dinowitz argued, there is good reason to make use of Midtown hotels. His main concern was making sure the city doesn’t pay too high a premium for those rooms.

“The city shouldn’t be paying, you know, $300 a night for example,” the Assemblyman said. “The question is, are we doing enough to protect people in general? So, I think there were some short-term issues that we have to look at to make sure that the homeless population is not suffering any more than they have to. But we have to protect everybody.”

At the municipal level, the city council wants to legislate its way into using hotel rooms for the homeless. Councilman Andrew Cohen expressed some concerns about this idea, however, saying the solution for New York’s homeless must be somewhere in the middle of shelters and hotels — even during the pandemic.

“I think that can be appropriate for some segment of the population. I don’t think that everybody who’s homeless belongs in a hotel room at the moment,” Cohen said.

“It’s a population that there is no one-size-fits-all solution for. There are some people who are high-functioning, relatively self-sufficient, who are homeless primarily due to economic circumstances. And those people could probably do OK in a hotel setting.”

And advocates of the mayor’s approach, like Banks, argue there is more than enough space in the shelter system to meet the needs of every individual while staying out of hotels.

“We have a bed for everybody. We have capacity in the shelter system, Banks said. “Gone are the days when the shelter system did not have enough beds for everyone.”