It's there whether you see it or not

A man asks pardon for interrupting the morning subway commute. He’s hungry and hopes someone can give him enough money for a sandwich.

At night, a small figure curls up in the doorway of an empty storefront — the blanket covering them woefully thin against the February air.

A rough-looking man asleep, head in his hands as he leans against the coffee shop table, while regular people rush by to work or day care or the gym — their lattes in one hand, a cell phone in the other.

That’s what comes to most peoples’ minds when they think of homelessness. It’s not the mom walking her two kids to school. Nor is it the sandwich shop employee, or the construction worker. It isn’t the college student with slightly disheveled clothes.

Yet they, too, have no home.

Every Monday, a handful of people without homes are brought to an emergency shelter run by the Riverdale-Yonkers Society for Ethical Culture in Fieldston. When there’s not enough room in city shelters, social workers place people in community shelters, like this one.

John Benfatti opened the shelter about 16 years ago, under neighborhood protest. With just six beds, it’s a small operation, he said. But it’s safety for the night. Guests get hot meals donated by Congregation Tehillah and the Hebrew Institute of Riverdale. They get to sleep on a real mattress with clean linens.

They like it there, Benfatti said.

“When somebody doesn’t show up who’s been coming on a regular basis, another person will tell us that they got housing or they got a job,” he said.

To stay, guests must be clean, free from substance abuse, and mentally sound. Many of them have jobs they work during the day. Some have families to take care of. Many don’t resemble the stereotypical image of the homeless.

Before the shelter found a home in Fieldston, a group from Riverdale Presbyterian Church pushed in the mid-1990s to shelter six men three nights a week at Riverdale Neighborhood House. It met with great public opposition. Kingsbridge Heights Community Center eventually offered accommodation for four nights — not the seven the group hoped for. After years without incident, the shelter at KHCC closed due to a lease technicality, leaving only the Ethical Culture meetinghouse in Fieldston to call home, Benfatti said.

Although the homeless population is small in the northwest Bronx, it still exists. There’s the sheltered homeless who may sit in libraries or coffee shops during the day. And then there are the sheltered homeless who depend on private or municipal organizations to provide a roof over their heads.

Many of them are young mothers. Some are regular working people who make too little to afford rent.

Shelters and transitional housing can help people survive until they get back on their feet. The city needs more of them, and most people acknowledge homelessness is a problem that won’t solve itself.

But that knowledge doesn’t mean people want solutions located in their neighborhood.

In 2014, people living and working within Community Board 8 were startled to learn the city was sheltering men in the Van Cortlandt Motel. The move caught elected officials by surprise. Broadway businesses nearby said the men’s presence affected their business. Neighbors pointed out the facility was near a group home, a school, and a future playground site.

After a community outcry, the city took action by moving the men out and converting the motel to family transitional housing.

In 2017, still accusing the city of lying about the motel, the community learned the newly built apartments at 5731 Broadway would become a transitional housing shelter for 83 families who would have access to social workers, vocational training, GED courses and children’s programs. The goal was to give homeless families the support they needed to find permanent housing.

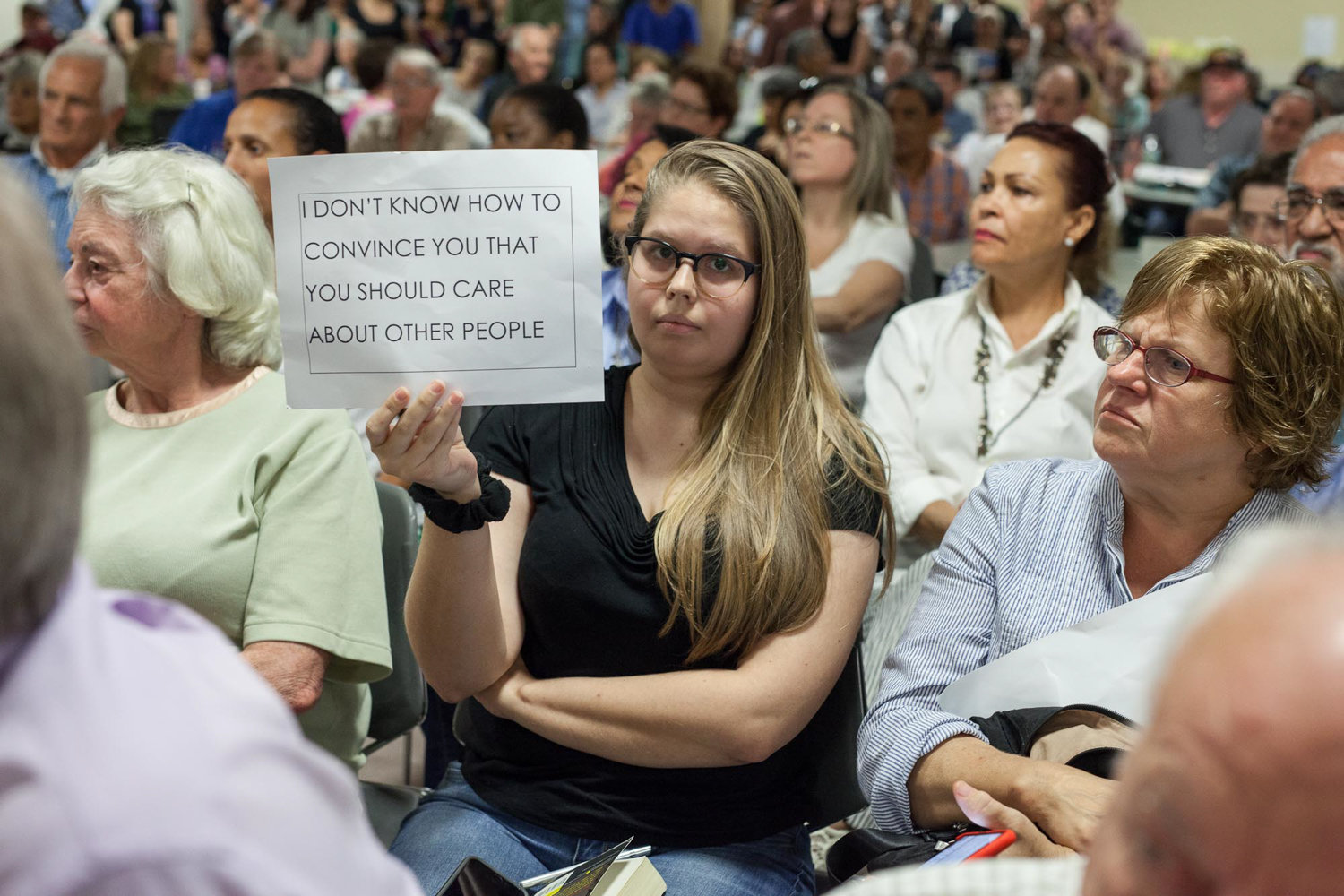

Some in the community were livid. Local petitions — for and against — revealed a sharp disagreement among neighbors. Supporters noted the facility would be for families that would be screened for substance abuse and criminal records. Opponents argued the city should have engaged the community about the project before it was fait accompli.

Others, shielded by the anonymity of the internet, stated the shelter would be filled with the stereotypical homeless — people the community never want to see near their block.

In the middle of that argument was Welcoming Neighbors Northwest Bronx, an organization that spoke in favor of the Broadway Family Plaza. Members argued the shelter’s target population is typically young mothers with a couple kids.

Most of them have jobs and just need a place to stay until they can find an apartment.

That wasn’t a consideration of a small number of vocal opponents, said Ivan Braun, a member of Welcoming Neighbors. Their hyperbolic predictions about drug addicts and hooligans were “classless and racist.”

Since its completion, there’s been no incident at the transitional shelter, he added. The fear mongering has been proven false because helping people find a home works.

“Off the top of my head, I would say Community Board 8 isn’t a hotspot for homelessness,” Braun said. “But it would be good if the community board stepped up and did more of its share to deal with the problem. That’s the point that myself and other members of Welcoming Neighbors made.”