Remembering a JFK High School basketball coaching legend, Johnny Mathis

Coach Mathis brought out the best in hoops stars while cementing legacy

The stories are endless with a unique ring to each. They belong to family, friends, and even competitors of a man who prioritized doing good deeds like he did when winning games. There were many more of those things to be realized — hence why days like last Thursday were hard for so many.

Johnny Mathis, the legendary boys basketball coach at John F. Kennedy High School for 35 years, passed away on Sept. 7 due to complications from multiple conditions including gout and arthritis. He did not respond to the treatment he received, according to his son J.C. Mathis.

Mathis was 80 years old.

“Mentally he was the same person,” J.C. says despite the struggles his father endured.

As the news spread, so did messages and tributes from those in the local hoops community wanting to honor Mathis. The outpouring is a testimony to what the beloved coach meant to so many.

“I spoke to him two or three weeks ago,” Benjamin N. Cardozo High School basketball coach Ron Naclerio told The Riverdale Press. “He is going to be missed.”

Naclerio called J.C. Mathis to confirm the reports of John Jr. ‘s passing, while friend and DeWitt Clinton great Nate “Tiny” Archibald and his family have been in close contact and are awaiting the release of funeral arrangements. Numerous other messages were either read or soon to be read by J.C.

By the end of 2021-22 season, Mathis could no longer bear the burden of using a cane and walker, and then a wheel chair, to perform his coaching duties. The physical toll caught up with him and it was time to say goodbye to his life’s calling. It marked the end of a mighty 35-year run that included 719 wins — third most in Public Schools Athletic League history — and yielded five PSAL Bronx championships and a pair of city titles.

The hardest exit from coaching comes when it is not on one’s own terms, Naclerio says. Mathis did not get the exit he wanted, nor deserved.

“At the end you want to not coach because it’s your decision,” Naclerio said. “If he was able to move around he would have still been coaching.”

J.C. Mathis is pulling many strings to stay on top of the messages coming in and out of his phone’s inbox. Every story about his father has made his day, especially the new ones he never heard. He learned that his father had kept people off the streets and away from drugs. One story came in about Mathis encouraging a young man with one arm to consider focusing on playing with his other arm. That specific act of kindness had a direct impact on keeping this person away

“He felt a higher responsibility to keep players off the street,” J.C. said.

The city title in 2000 was won with J.C. starring for JFK, and is a memory which will forever make him think of his father. There was so much to be thankful for during those times, says J.C.

The commute from the family’s home in the Bedford Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn to JFK every school day always gave them ample time to catch up on basketball and the state of affairs of the JFK program.

“On the way home we would listen whatever sports team was playing after practice,” said J.C., who played basketball for University of Virginia and University of Michigan. “We were as close as a father and son could be”

To play for Mathis also meant a commitment to get in shape. Back then, practices during the week were three hours before school policy eventually reduced the length. All of that on top of getting homework done was a tall task while playing for Mathis.

For years, Mathis never cut players no matter their skill level. That practice was not the norm at PSAL schools, and it even led to questions from other notable PSAL coaches like Dwayne “Tiny” Morton of Abraham Lincoln High School.

Mathis wanted to win, but not at the expense of doing the right thing. He wanted his team prepared regardless of the opposition, which was a lesson he learned from the coach he idolized most: John Wooden.

“He had the philosophy that John Wooden had about preparing his own team,” J.C. said.

He coached like few around here could, too.

Before entering the championship years at JFK, one time Mathis came back from an annual coaches clinic — still held during the NCAA Final Four weekend — with a defensive concept he considered to be a game-changer. It was a 1-1-3 and a successful ingredient for his championship teams.

“I always thought it was 2-3 zone because I had problems against it,” Naclerio joked. “It was a high school version of what John Chaney ran at Temple.”

J.C. admits the higher competition on the PSAL circuit in recent years made the margin of error even smaller, especially against fellow Bronx foe Wings Academy.

J.C. had joined the JFK staff to assist his father on the sideline, and together, they produced one last run to a PSAL Bronx title in 2019 that was highlighted by an upset over Wings.

It felt like a final hoorah in Mathis’ tenure, despite him still coaching through the pandemic.

“To go through the health issues to be an underdog again, and to beat Wings on the route there was really special to him,” J.C. said.

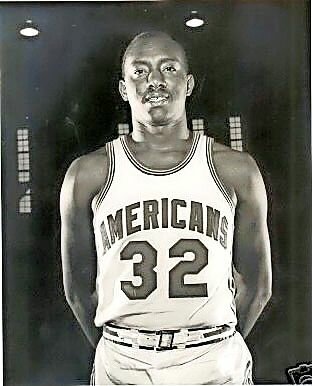

Mathis enjoyed much success during his own playing days, too. He carved out a four-year stint at Savannah State University, an ex Division One school in his home state of Georgia. He parlayed his scoring prowess, including a senior year average of 27 points per game, into a professional career mostly remembered for a brief stint with the New Jersey Americans of the old-time American Basketball Association. The franchise eventually became today’s Brooklyn Nets.

His exploits on the hardwood helped forge the relationship with Archibald. The two showcased their skills side by side in the Rucker Pro League and before that crossed paths during a training camp for the Cincinnati Royals of the ABA.

That bond remained close and Archibald would stop by practice at JFK to speak to the players. In quite the Mathis fashion, he always called for a segment centered around the former Boston Celtics star offering tips to the JFK guards.

“My father would stop practice and ‘Tiny’ would work with them,” J.C. recalled.

The formative years growing up in Georgia helped shape Mathis’ worldview. Growing up in Jim Crow South taught him to value what he had and to be the bigger person when life was not always fair.

He was an avid reader of the Bible as a form of daily ritual, which dated as far back as J.C. can remember. While some subject themselves to reading it once, Mathis read the bible seven times in his life.

Mathis wanted to be on the margins with those in need. For seven years, he was a head coach in the New York Wheelchair High School Classic for kids who were able to play basketball despite their disability. In addition to coaching, he answered the call as a senior recreational therapist for almost 30 years at Bronx Psychiatric Center.

He did these things because everyone deserved a seat at the table in Mathis’ eyes. His ethic was priceless and his legacy left without any doubt. In 2009, JFK chose to name their gym “Coach Mathis Arena” so that a part of their legend resides there forever.

Mathis is survived by his wife, Marsha, and four children, Dina, Sheila, J.C. and Jarrett, as well as a grandson, Johnny IV.